Wabanaki cultural heritage, history a woven theme in ‘IT: Welcome to Derry’

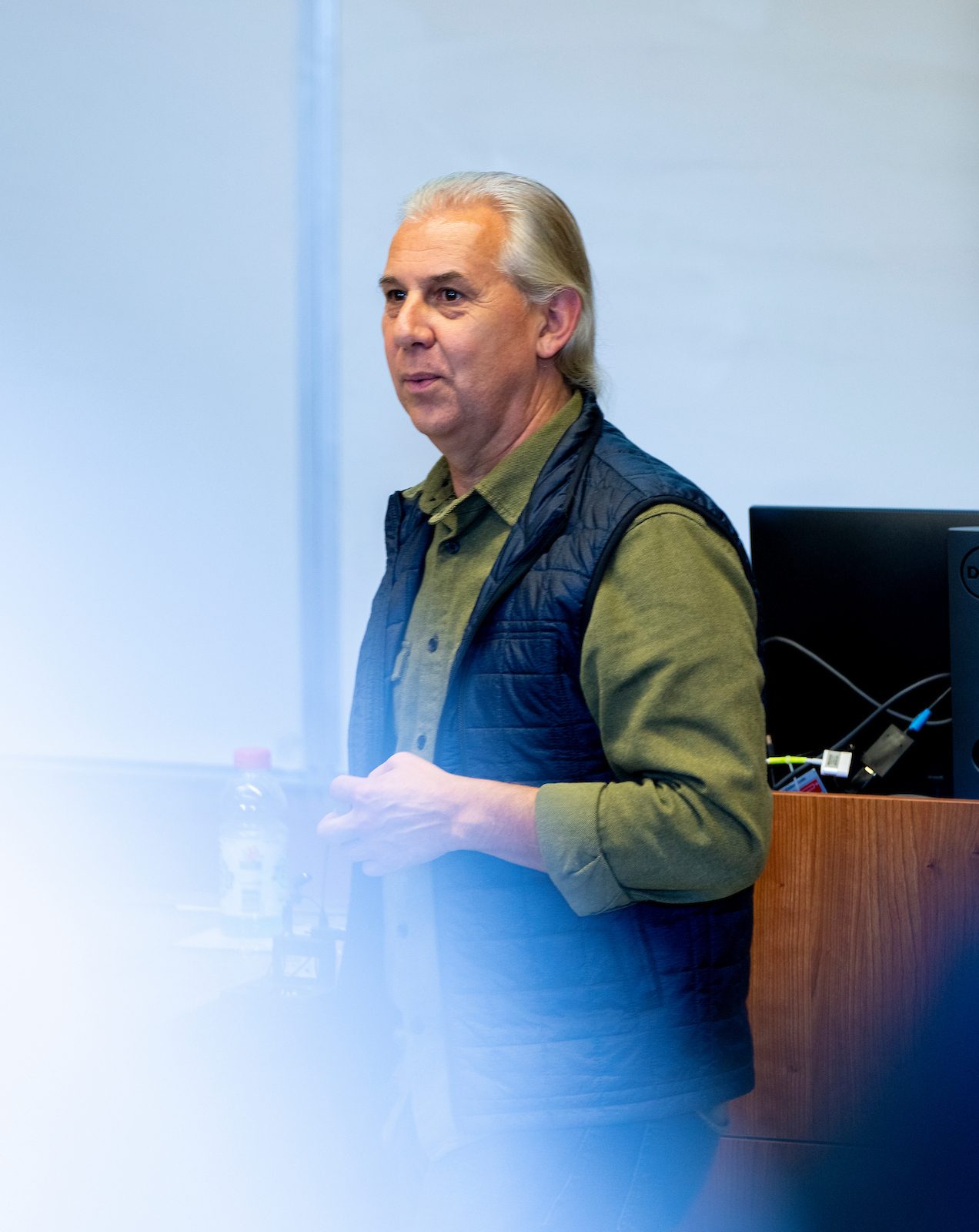

Indigenous characters and storylines are often misrepresented in film, television and pop culture. John Bear Mitchell, a University of Maine lecturer in Wabanaki studies, set out to change that as a consultant for HBO’s “IT: Welcome to Derry,” based on Stephen King’s 1986 novel.

Mitchell worked on the production team for the miniseries to help develop a theme that accurately represents the Wabanaki people. He said work began four years ago on the project, which aired its first episode on HBO Sunday, Oct. 26.

Since then, he’s collaborated with nearly everyone in production — from writers and actors to camera operators — to ensure Indigenous storylines and characters in the show weren’t misrepresented.

“I looked at reframing horror by incorporating native experiences and addressing historical trauma,” Mitchell said. “I wanted to show horror is a tool for racial injustice, and I wanted to address flawed portrayals of Indigenous people.”

Set in the fictional town of Derry, Maine, in 1962, the series delves deeper into the lore of Pennywise the Clown, the monster who terrorizes the town every 27 years — until a group known as the Losers Club confronts him decades later in “IT: Chapter Two.”

While “Chapter Two” included brief references to a local Indigenous tribe, “Welcome to Derry” expands that thread as it explores the origin story of Pennywise. The show’s character Rose, played by Kimberly Guerrero, is connected to Derry’s Indigenous mythology.

“It’s an honor and a responsibility,” Guerrero said in an exclusive interview with Parade. “To bring Indigenous lore, real history, real people … to show that they were there, that they loved and lost … that’s powerful.”

King, a Bangor native, has long drawn inspiration from Maine’s people and places, with Derry serving as a fictional stand-in for his hometown and surrounding communities.

We asked Mitchell about his experiences working on the show in the following Q&A.

How did you get involved in the show?

I have 22 years of background working with film productions. It first started out in 2003 when I worked on a PBS and BBC series called “Colonial House,” which was a living history show depicting the year 1624. Over the years, I’ve worked with or consulted on several movies. I was hired by director Gus Van Sant; Todd Field, a director for another project; and then “IT: Welcome to Derry” was with Andy and Barbara Muschietti, who also made the last two “IT” movies.

They reached out to me based on previous work that I’ve done, and they were looking at incorporating an Indigenous perspective into the series. We worked basically for four years on season one because we had writer strikes, we had actor strikes and we had COVID-19.

I worked with props, set, hair and makeup, producers, directors, writers and show runners. There wasn’t one aspect of “Welcome to Derry” that I did not work on. I was there for five weeks worth of filming in the summer of 2024, when we filmed in Toronto and surrounding local areas.

What was your role in production?

My main goal was to tell a story, make connections and essentially address various issues within the theme of the show. I served as a cultural advisor and a consultant to ensure that the story was told with reverence and accuracy. How do we get historical? How do we address historical injustices? How do we address colonization through horror?

We’ve taken a fictional story, but we’re telling a story within that story. We had a really good cast I got to work with — a top of the line cast, which if you watch the series, you’ll see. I worked with a lot of the actors to sort of help them understand the Wabanaki people and to represent them in a way that they felt was honorable. Even though this is fiction, we want to be telling a story that doesn’t demean or discourage and is accurate in how we’re portrayed as a people.

Can you give an example of how you helped create a narrative that honorably represented the Wabanaki people?

The major catalyst behind what I contributed to the show is that we (the Wabanaki people) are compassionate. I wanted it to accurately represent that instead of leaning into stereotypes of hostility and anger. We aim to tell a compassionate story, reacting to situations in a compassionate and understanding way and to be helpful but not to be subservient.

When we look at immigration or colonization, we followed the path of respect. Everybody should have the ability to eat, to be housed, to pray in any way they want. So why not let these people land on our shores? That’s the compassion that we showed, and it backfired. What happened in the meantime? Did we lose our compassion? No, we didn’t lose our compassion. We actually kept it, and we’re dealing with situations that worked against us in a way.

That’s what I wanted to portray when we did the film. They gave us an opportunity to tell the story within a story, and we took that opportunity. We really focused on historical context. I looked at reframing horror by incorporating native experiences and addressing historical trauma. I wanted to show horror is a tool for racial injustice, and I wanted to address flawed portrayals of Indigenous people.

How big a part of the show is this sub storyline about Indigenous peoples?

It’s a theme. It’s threaded, and it will become completely obvious how it’s threaded once the series airs completely.

Contact: Ashley Yates; ashley.depew@maine.edu