Breadth of scope

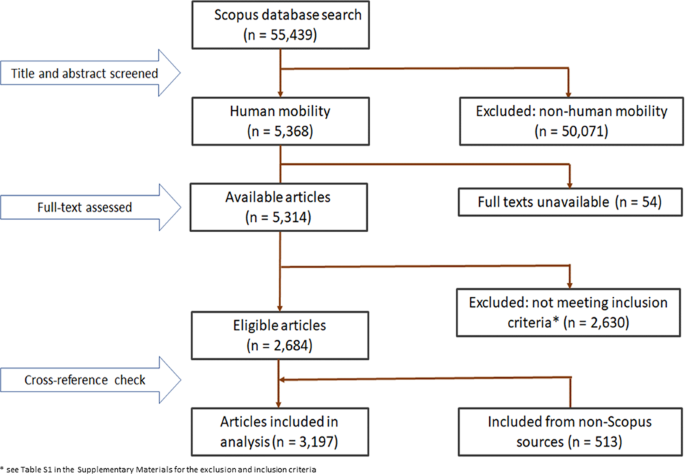

Using unsupervised machine-based topic modelling to extract and classify meaning from documents, which underpins the novelty of the current study within the field of environmental impacts on human mobility, has three major beneficial characteristics—the number of documents that can be analysed, the impartiality of document selection once selection rules have been established, and, given its automation, the breadth of analysis scope (Dörre et al., 1999). As a consequence, we were able to analyse 3197 peer-reviewed articles selected from Scopus or bibliographically connected to such documents, about twice as many as any attempted previously using narrative approaches (Piguet et al., 2018).

The two most striking results of the analysis are a consequence of the breadth of scope. The first was the diversity of topics—that 37 topics in five clusters should emerge emphasises both the ubiquity of environmental influences on human mobility behaviours and their complexity. The diversity materialised partly because we did not assume a direction to the relationship between environmental change and mobility; climate change for example can be either a push or a pull factor depending on the context. The variety demonstrates again how inappropriate it is to characterise people moving for reasons related to environmental change as ‘refugees’ (McAdam, 2013)—the term appears as a key word in only one of the topics (33).

The second notable finding was the deep linguistic dichotomy between the Impact and Adaptation research themes. The result suggests a lack of communication between two streams of scholarship that might otherwise have much to share. The Impact theme consists of a rich and diverse body of literature on mobility along the continuum from voluntary to involuntary. The Adaptation theme includes scholarship examining governance, disaster planning and mobility associated with farming, often describing voluntary planned movement, and often to the advantage of those moving. That the topic modelling separated the two so definitively suggests that the two fields of research may draw little on the findings of each other—literature on adaptive planning that builds on the experience of research on involuntary mobility might have been expected to fall between the two research poles.

The distinction between the two themes also reflects an existing distinction between research strands, namely between those studies primarily addressing mobility as a response to climate and environmental change, conceiving mobility as a symptom of failed (in situ) adaptation, and those that address the potential of mobility as an adaptive strategy (e.g. Singh and Basu, 2020). The depth of the dichotomy between the two themes illustrates both the strength and weakness of unsupervised topic modelling. In real life the ontology of the human mobility–environment nexus is complex and impact and adaptation overlap. However, the language adopted in the literature to date has meant such complexity is not recognised by the language-based machine-learning models used here. In future, the dichotomy may be less pronounced either because there is more research that connects the two themes, or there is a greater emphasis on the precision of the language employed so that the continuum between impact and adaptation is more apparent to unsupervised analysis.

As it is, there is some reflection of the overlap in the analyses. Thus, articles within the Impact theme also consider adaptation behaviour and mobility as adaptation strategies in response to adverse environmental and climatic conditions, just as articles within the Adaptation theme mention the impacts of climate change and environmental hazards. The difference lies in the main focus of the research and the emphasis given to different topics in the interpretation of the results. Within themes, the clusters are more closely related but nevertheless reveal key differences in research emphasis. Urban migration, for example, is all within the Residential cluster and is mostly related to slow-onset hazards such as heat and pollution. Research in these areas emerges as distinct from social vulnerability, which tends to emphasise low-income countries and farming societies (Cattaneo et al., 2019; Piguet et al., 2018). The lack of connection between sea-level rise and urban mobility suggests that research on managed retreat from coastal cities (Mach and Siders, 2021) is in its infancy, although ‘retreat’ is among the 50 key words for ‘Climate change adaptation policy’ (topic 37).

Many topics, and the largest cluster (Vulnerability), do not actually include a mobility-related term among the most important terms even though related to the environment–mobility nexus. This emphasises that human mobility is either just one aspect of behaviour research in the articles or that, for many hazards, mobility is not a viable response. For example, ‘South–North migration’ (topic 32) includes income and labour as key words but not environment or climate-related factors. This means that while research in this area acknowledges that environmental factors might trigger emigration from low-income countries, these have been less important than economic drivers (e.g. Hugo, 2006). Indeed, often the people most vulnerable to environmental change are most likely to be legally, financially and socially prevented from moving (Black et al., 2013).

Climate change is considered patchily across the corpus of literature, featured in only 34% of all articles. The Disaster cluster, for example, makes no mention of climate change. Literature in this cluster is strongly focussed on short-term responses to sudden-onset hazards such as cyclones and floods and appears to make few links to underlying drivers that make such responses increasingly necessary. While migration often implies a long-term and permanent action, evacuation is usually seen as a short-term response, resulting in temporary displacement until people could return after the situation stabilises (e.g. Black et al., 2013). Overall, the topic modelling did not identify research that considered the temporal or spatial scale of mobility. While some topics include countries or regions among their most important words (topics 1, 3, 5, 6, 10, 18, 20, 22, 32), language relating to the origin, direction or destination of mobility is not sufficiently salient to emerge from topic modelling.

Other sets of words appear across multiple topics but with different connotations. For example, ‘Environmental impacts of human mobility’ (topic 9) shares many key words with ‘Environment driven migration’ (topic 10). Although the algorithms underpinning the machine learning classified the research into different topics, further screening is needed to extract the nuanced difference between these topics. A similar example is the differences between ‘Impact of amenity migration’ (topic 7) and ‘Amenity migration’ (topic 20). The former is within the Vulnerability cluster and considers the negative environmental impacts of ‘green migration’ and the impact on rural societies from people in-migrating to the countryside for lifestyle and amenity purposes (e.g. Jones et al., 2003) or the environmental impact of people in-migrating to conservation areas (e.g. Salerno et al., 2014). The latter (topic 20) is clustered with other Residential topics and includes research on people moving to places with higher environmental quality (e.g. Gurran and Blakely, 2007).

Perhaps surprisingly, there were no major trends over the last 30 years in the diversity of topics on which there was peer-reviewed research. This is partly because the proliferation of research in the last half of the period swamps the influence of earlier research and maybe partly because 30 years is too short a time for some of the trends to become apparent. The one area which has seen a disproportionately large increase in research interest relates to Governance within the Adaptation theme, which is likely to be associated with national legislative responses to the Paris Agreement (Iacobuta et al., 2018).

Research gaps

One means to identify possible research gaps is to look for the mirror-image of topics. Several imbalances stand out. For example, there is a great deal of research on how environmental change has driven human mobility, but only one topic on how mobility is directly affecting the environment (topic 9), whether at the point of origin or the destination. This topic’s prevalence is even declining (Fig. 4) which is in stark contrast to declining habitability of some places which might trigger relocation of many people, planned or unplanned (Horton et al., 2021), with environmental, social and infrastructure consequences for potential destinations. There is mention of impacts under other topics, such as the environmental impacts of large-scale projects such as dams (topic 4) and impacts of amenity migration, which are large of socio-economic nature (topic 7), but the main emphasis of these articles is not on migration.

Similarly, there is research on migration being induced by the health impacts of environmental degradation (topics 15 and 37) but there seems to be none on whether the migration-related health benefits are actually realised, partly for lack of adequate longitudinal studies (Vinke and Hoffmann, 2020). The way that mental health influences people’s migration decisions serve as another area in need of more attention (Kelman et al., 2021). Indeed, there was little research identified in the corpus of literature to 2021 on the trajectories of people who have moved for environmental reasons, whether voluntarily or under duress.

The patchy use of spatial or temporal words also reveals potential research gaps. Disaster risk management, for example, appears to consider only evacuation not what happens to people who decide never to return. Other terms common in social research, such as Indigenous and gender, appear rarely. The term Indigenous came up in two topics, one on displacement forced by development (topic 12), the other related to Amazon deforestation (topic 22), both within the Impact theme. Indigenous is not mentioned in the top 50 words in topics within the Adaptation theme. Similarly, only one topic (topic 21 within the Impact theme) includes women and gender as keywords, pointing to a lack of gender consideration within the Adaptation literature, whether of women or men, as noted by another review (Obokata et al., 2014). The apparent lack of attention to women extends to relative disinterest in the mobility decisions of families or how families are affected by their members moving. There is one topic on post-disaster resilience (topic 35) that considers, for example, the role of family in wildfire evacuation (Asfaw et al., 2019) or how families cope with the aftermath of disasters by sending out one family member permanently to search for alternative employment opportunities (Mallick, 2014).

Finally, there seems to be limited literature on adaptative capacity with just three topics, one in each cluster of the Adaptation theme: the first investigates people’s capacity to cope with sudden-onset (topic 27), the second slow-onset disasters (topic 25), and the third climate change adaptation policy (topic 37).

Study limitation

We identified two main limitations, one related to the applied method, one related to the underlying systematic literature review. While the topic modelling itself was unsupervised and not subjective in terms of the number of topics and the terms, the interpretation of the topics must necessarily involve human judgement. Without expert opinion and context to interpret the results of machine-based topic modelling, they provide little meaning (Philipps, 2018). We used the 50 most frequent words within each topic to assign a label to each topic and a theme to the clusters of similar topics. Sometimes the words themselves did not provide enough context and detail to convey the explicit ideas of the topics (Aggarwal and Zhai, 2012). This might have led to bias and incorrect conclusions (Hillard et al. 2008). When interpreting the topics, we therefore double-checked the articles within each topic and used them to label the topics, particularly when topics had similar keywords.

Overly detailed or complex topics, as well as infrequent topics, may not be detected in topic models (Aggarwal and Zhai, 2012). LDA assumes documents are exchangeable across the corpus, which may not be reasonable if, for example, experts can identify that documents have clear differences (Blei et al., 2003). Similarly, topic modelling must assess similar documents with consistent themes and word use. If this is not the case, then results may be skewed (Hillard et al., 2008). Conversely, it can be difficult to assign words and documents to topics if the texts are too similar to one another (Aggarwal and Zhai, 2012; Hillard et al., 2008). The only way to combat these limitations, as noted above, is for researchers to understand current research and the texts that are being analysed.

Another potential limitation concerns the literature search. There is the possibility that we failed to include relevant articles, for example, those not peer-reviewed and published in Scopus, those not in English and those not using the key search words in the abstract or title. We used cross-reference checks to minimise this limitation and added a substantial amount of literature not initially picked up (513). Also, the large number of articles included in the text analysis gives us great confidence in the validity of the results.