In 1904, under President Porfirio Díaz, American capital rapidly expanded into Mexico’s mines, oil, and railroads. During Yucatán’s henequén boom, the “green gold” made the state one of the richest in the country at the turn of the 20th century. This economic surge created a demand for imported labor — setting the stage for immigration from Asia. Across the Pacific, Korea was entering a crisis of its own. Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) made the loss of Korean sovereignty seem inevitable. While activists resisted colonial rule, many Koreans sought survival through emigration. Newspapers at the time promised a better life on plantations in California, Hawaii and Mexico.

That same year, on May 14, 1905, 1033 Koreans boarded the British ship Ilford at Jemulpo Port (now Incheon) and arrived at Progreso, Yucatán. They came as contract laborers for the haciendas. Five years later, in 1910, Korea was formally annexed by Japan, leaving them stateless. As the Mexican Revolution dismantled the plantation system, they lost their only source of livelihood. When the hacienda economy collapsed in 1921, about 300 Koreans embarked on a new journey to Cuba, where they found work on sugarcane plantations.

The 1973 book “Memorias de la Vida y Obra de los Coreanos en México desde Yucatán” by José Sánchez-Pac documents the story of the Korean diaspora in Yucatán. It traces his parents’ years of forced labor under harsh conditions. Martha Lim Kim, a fourth-generation descendant of Korean immigrants in Cuba, tells how the community preserved its identity through her book “Coreanos en Cuba,” reflecting a shared spirit of Korean resilience and Cuban solidarity. Despite the poverty that followed the collapse of the sugar market, Koreans in Cuba continued to send patriotic funds to support Korea’s independence movement.

The seeds of immigrant success

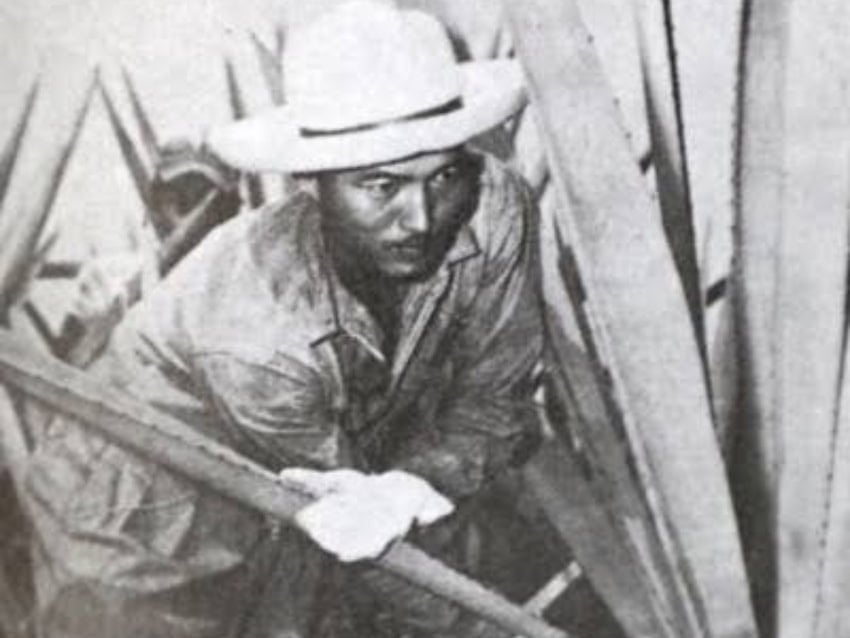

Kim Ik-joo (Joaquín Kim, 1890–1956) boarded the Ilford at the age of 15 and began his new life as a contract laborer at the Chocholá hacienda in Mérida. After four years of labor, he moved to Tampico, where he started a tea business and later opened Mexico’s first Korean-style duplex cafeteria. Building upon his financial success, Kim devoted himself to the vision of a self-governing Republic of Korea. He became a unifying figure among Koreans scattered across the continent until he died in Mexico City, shortly after the Korean War.

Survival in exile: education above all else

Lacking access to formal education, the first generation of Korean immigrants learned new languages and adapted to a new culture. Working alongside indigenous Maya laborers on the haciendas, they first learned the Mayan language before Spanish. Recognizing the power of learning, Korean community leaders in Mexico placed education above all else. Determined to create their own opportunities for education, they established schools across haciendas and marketplaces throughout Yucatán. Language and tradition became their anchor of identity, helping the first Koreans in Mexico gradually open doors to Mexican society.

In 1910, the first Korean national school, Sung-Mu School (숭무학교), was established. The school taught Spanish and the Korean language and history, as well as traditional martial arts such as Taekwondo. Soon after, Jin-Sung School (진성학교) was founded at the Itzincab plantation, Ui-Seong School (의성학교) in Oxtapacab, and Ban-Do School (반도학교) in Lepa. In 1917, Hae-Dong School (해동학교) in San Sebastián became the first Korean school to receive official recognition from Mexico’s Ministry of Education. Earlier in 2025, a commemorative plaque was unveiled at San Benito Market, honoring more than a century of cross-cultural legacy by Jung Gab-hwan, the chairman of the Institute for Korean Historical Issues (Latin America Branch).

Mérida: beyond migration, a shared legacy

Today, Mérida is home to the Korean Descendants Association of Mérida, chaired by Duran Kong. As the capital of Yucatán, the city has embraced this history as part of its identity, making Mérida a unique place where the past and present of Korea and Mexico coexist. Landmarks across the city invite visitors to this shared heritage. The Centennial Monument of Korean Immigration, engraved with the names of all 1033 young individuals who first arrived in Mexico, stands as a tribute to the pioneers of the Korean diaspora.

Beside the monument stands the Hospital de la Amistad Corea–México (Korea–Mexico Friendship Hospital), built on land donated by the state of Yucatán in 2005. Today, this public hospital serves as a modest pediatric facility equipped through Korean cooperation programs.

Avenida República de Corea honors the enduring history between the two nations. In 2021, Korean artist Yoo Young-ho’s blue sculpture “Greetingman” was installed along the avenue. Depicting a traditional Korean bow of gratitude, the figure symbolizes mutual respect between the two cultures. The nearby Esquina El Chemulpo, named after the port of Incheon, carries a poignant memory of a man who once cried out the name of his homeland at this corner — a voice that still echoes through the city.

When Korean history meets Mexican muralism

The Museo Conmemorativo de la Inmigración Coreana opened in 2005 at the Centro Histórico, Mérida, under the direction of Dolores García Escalante. El Muro de la Memoria (Wall of Memory) is a collaborative mural project by Mexico City-based Korean artist Long Bae and Mexican muralist Laite. Incorporating Korea’s traditional dancheong patterns with Mexican cactus motifs, the mural commemorates the 120th anniversary of Korean immigration to Mexico, a country where muralism has long served as a language of collective memory.

Echoes across generations and continents

During a time of rising anti-immigrant sentiment, the story of the Koreans who arrived in Yucatán in 1905 reminds us that migration is not only about survival, but about building sustainable communities grounded in hope. Today, K-pop’s global reach has forged new cultural bridges between Korea and Mexico, allowing those early voices of resilience to continue inspiring generations across both nations. Carrying that legacy forward, HYBE Entertainment, a global K-pop powerhouse, embodies how pop culture can transcend borders and generations alike.

Beyond borders: HYBE’s new chapter in Latin America

In 2023, HYBE launched its Latin America headquarters in Mexico City, marking a major milestone in its mission to globalize K-pop through diversity. As part of this initiative, the company introduced Santos Bravos, its first reality competition aimed at forming a Latin American boy band. Santos Bravos premiered on YouTube in August 2025, with new episodes released weekly.

The program’s mentors include Kenny Ortega, the acclaimed choreographer best known for High School Musical; Johnny Goldstein, the hitmaking producer who has collaborated with Shakira; and RAab Stevenson, the renowned vocal coach of Justin Timberlake and Rihanna.

Sixteen young performers from Mexico to Spain have come together on one stage, embodying the rise of K-pop’s global influence. Among them is Kauê Penna, the Brazilian prodigy who won The Voice Kids Brazil in 2020. Together, they unite world-class expertise with emerging new talent to shape the next generation of Latin K-pop artists. Reviving the educational spirit of Korea’s early pioneers, this project fuses the discipline of the K-pop training system with the passion and artistic flair of Latin culture, forging a bold new global K-pop movement.

Rosario Bae is a Korean freelance journalist