This is a subanalysis of the PNS2019 database, a nationwide, cross-sectional, door-to-door survey of a representative sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized Brazilian population. The survey was conducted by the Ministry of Health in partnership with the Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz) and Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) between August 2019 and March 2020.

PNS2019 adopted a complex sampling design [31], based on three-stage cluster sampling with stratification of primary sampling units (PSU) from census tracts or sets of tracts and selection of PSUs for the main sample. Households were selected from the National Register of Addresses for Statistical Purposes and finally, the definition of the PSU sample size [31]. The survey sampling weights were defined considering the weight of the corresponding PSU. Corrections for non-response and calibration of the estimates were made according to the population totals estimated by the IBGE [31].

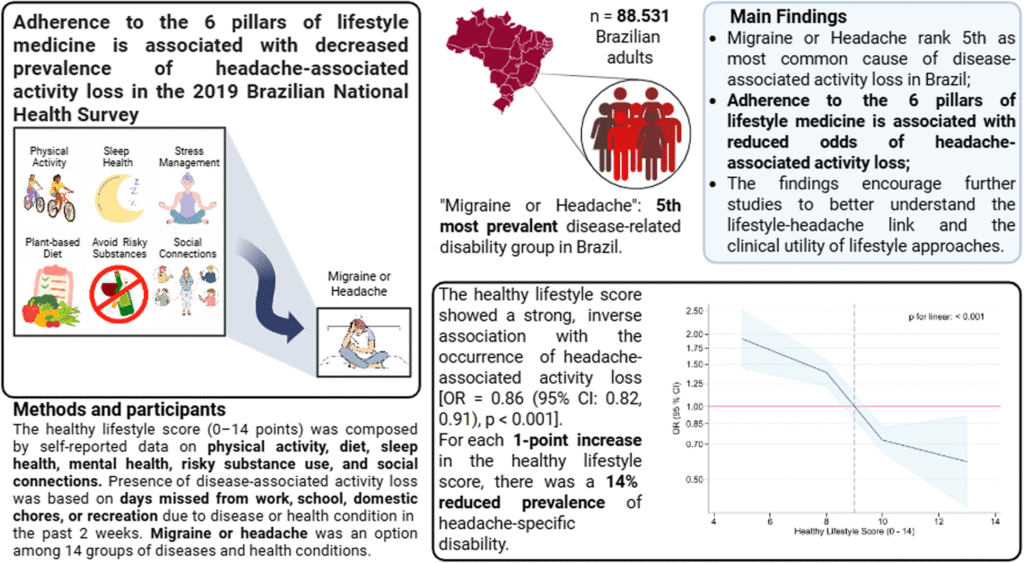

The PNS2019 sample consisted of 8,015 PSUs, composing 574 strata. In the sample with individual responses from the dwellers, there were 94,111 household visits, with 90,846 participants interviewed (96.5% response rate). In this study, the data were obtained from Brazilian adults ≥ 18 years old who responded to questions about general sociodemographic information, health service utilization (Module J), lifestyle behavior (Module P), and chronic diseases (Module Q).

The National Research Ethics Committee (#3.529.376) has reviewed and approved PNS2019. All participants gave written consent before enrollment.

Assessment of variables

Outcomes: headache-associated activity loss

Disease-associated activity loss was assessed through a series of questions about the number of days in the past two weeks during which individuals were unable to carry out their usual daily activities (work, school, household tasks, or recreation) due to disease or health condition. Responses were collected through single-choice questions, including 14 categories of major diseases or health conditions. Among these,”Headache or Migraine”was listed as an option and here we defined it as headache-associated activity loss. Table 1 presents the full set of questions, response options, and the complete list of conditions assessed.

Exposure to lifestyle factors: the healthy lifestyle score

The healthy lifestyle score was developed based on the six pillars of lifestyle medicine: physical activity, sleep health, diet, mental health symptoms, risky substances, and social connection. It incorporated variables from the PNS 2019, including leisure-time physical activity (LTPA); dietary patterns such as consumption of whole foods, vegetables, fruits, and fish; intake of ultra-processed, junk, and fast foods; sleep problem symptoms; alcohol consumption; smoking status; and participation in social activities like cultural, sports, recreational, or religious group events. Table 2 summarizes the components of the 6-pillar framework and their respective scoring system.

Lifestyle components were scored as 0, 1, or 2 points, corresponding to the poorest (low adherence), intermediate (moderate adherence), or healthiest (high adherence) options, respectively, depending on exposure levels. For diet and social connection, which consisted of multiple questions, unweighted mean scores were calculated. Scores for unhealthy food groups were inverted, thus, the values of 0 and 2 points represented the highest and lowest consumption frequencies, respectively (Table 2).

Given the significant impact of alcohol consumption [32] and smoking [33] on mortality and disease burden, these factors were analyzed separately under the “risky substances” pillar. Consequently, the total healthy lifestyle score included seven items, ranging from 0 to 14 points as the unweighted sum. Higher scores reflected a healthier lifestyle profile. The details of the assessment of each component and the methodology of the scoring system adopted for each pillar of lifestyle medicine are described in the following subsections.

Assessment of the 6-pillar lifestyle medicine framework

Physical activity

Leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) was the domain of interest due to its more consistent associations with reduced CVDs and CMB risk [34,35,36]. LTPA was surveyed by the following questions: (i) “In the previous 3 months, did you engage in any physical exercise or sport?” (excluding physiotherapy, yes/no answer options); (ii) “How many days per week do you practice any physical exercise or sport?” (never/less than once per week, or 1–7 days options); (iii) “In general, how much time in hours do you spend performing physical exercise or sport?”; and (iv) “In general, how much time in minutes do you spend performing physical exercise or sport?”. The total weekly minutes of leisure-time physical activity were calculated and categorized according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2020 physical activity guidelines [37]. Participants were defined as “active” if they met at least one of the following criteria: engaging in a minimum of 150 min per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity or 75 min per week of vigorous physical activity. Those who reported no physical activity were defined as “inactive.” Participants who engaged in physical activity but did not meet the thresholds for the “active” category were defined as “somewhat active”[37]. The score values of 0, 1, and 2 were attributed to inactive, somewhat active, and active, respectively.

Diet

Dietary patterns were assessed using the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), which enquires about the frequency food consumption over the past week (0 to 7 days). For our scoring, we selected the following food groups: (a) beans; (b) raw and cooked vegetables (lettuce, carrots, tomato, chayote, collard greens, eggplants, zucchini, etc.); (c) fruits; (d) fish; (e) sodas; (f) sweets (such as cakes, pies, chocolates, candies, cookies, or sweet biscuits); and (g) meals replaced with sandwiches, hot dogs, snacks, or pizzas. Each food group was assigned a score ranging from 0 to 2. For healthy food groups (a to d), a weekly consumption frequency of 0 to 1 time was scored as 0, 2 to 5 times as 1, and 6 to 7 times as 2. In contrast, for unhealthy food groups (e to g), a weekly intake of 0 to 1 time was scored as 2, 2 to 5 times as 1, and 6 to 7 times as 0. The diet score was calculated as the unweighted average of the scores across all food groups.

Sleep

The categorization of sleep health was based on the questions “In the past 2 weeks did you take any sleep medicine?” (answer options were yes/no) and the item 3 of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)”In the past two weeks, how often have you had sleep problems, such as difficulty falling asleep, waking up frequently during the night, or sleeping more than usual?”with response options and their respective values being “Not at all” (0)“Several days”(1), “More than half the days”(2) or “Almost every day”(3) [38]. The score value of 0 was assigned to participants who reported taking sleep medicine and/or experiencing sleep problems “More than half the days” or “Almost every day.” A value of 1 was given to respondents reporting sleep problems on “Several days,” while a value of 2 was attributed to respondents reporting no sleep problems (“Not at all”).

Mental health

Because PNS 2019 has no specific question on stress, the pillar of mental health was operationalized based on the PHQ-9 score, which has been translated and validated for the Brazilian population [38, 39]. The PHQ-9 assesses the severity of depression with nine questions about symptoms over the past two weeks, using a 4-point Likert scale. Depression severity is categorized into five levels based on the PHQ-9 scores: minimal or none (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19), and severe (20–27). For our healthy lifestyle scoring system, the following PHQ-9 categories/values were assigned: minimal or none (0–4) = 2, mild (5–9) = 1, and scores > 9 = 0.

Risky substances

Smoking status

Current smoking status was assessed by the questions: “Do you currently smoke any tobacco products?” or “Did you use to smoke any tobacco products?”. Answer options for both questions were “yes” or “no”. The score value of 0 was assigned to current smokers, the value of 1 was assigned to former smokers, and the value of 2 was assigned to non-smokers.

Alcohol consumption

We used the question “How often do you usually consume any alcoholic beverage?” to assess drinking habits. Response options were “never”, “less than once/month”, and “once or more/month”. The score value of 0 was assigned to the drinking frequency “once or more/month”, the value of 1 was assigned to “less than once/month”, and the value of 2 was assigned to abstemious participants (“never”).

Social connections

We selected the two following questions to assess social connection: “In the past 12 months, how often have you met with others to engage in sports, recreational, or cultural activities?” and “In the past 12 months, how often have you attended collective activities of your religion or another religion, excluding situations such as weddings, baptisms, or funerals?”. The religious attendance was selected as a social connection component, based on the high prevalence of religious affiliation in Brazil and as a major social activity with potential impact on health [40,41,42,43]. For both questions, response options were: “More than once a week”, “Once a week”, “From 2 to 3 times a month”, “A few times a year”, “Once a year”, “Never”. The score values of 0, 1, and 2 were assigned to the frequencies “Never or once a year”, “Sometimes every year to 3 times a month”, and “Weekly or more”, respectively. The social connection score was calculated as the unweighted average score of the two questions.

Covariates: sociodemographic factors

Sociodemographic variables included the 5 main geopolitical regions of Brazil (North, Northeast, Central West, Southeast, and South), age, sex assigned at birth (Female, Male), housing place (Urban, or Rural), self-reported skin color (White, Black, Brown, Others – Asian, Indigenous) [5], marital status (Single, Married, Separated/Divorced, or Widower), household Income (per capita), separated into quartiles, Q4 Income (lowest), Q3 Income, Q2 Income, Q1 Income (highest), educational attainment (No formal/incomplete primary, Complete primary, Complete high school, and Complete college), labor force status (Inside the labor force, Outside the labor force), excluding income from the pension, and job status (Employed or Unemployed). People inside the labor force were defined as working-aged people employed or unemployed and outside the labor force. People outside the labor force were defined as working-aged people not classed as employed or unemployed.

Statistics

The population estimates were based on the number of strata, the number of selected PSUs in each stratum, and the number of households and residents included in the PSU and their respective expansion factors and sample weighting. The data on weights, number of PSUs, and strata were provided in the dictionary of variables file along with the PNS2019 database. In the PNS2019 survey, it was necessary to define expansion factors or sample weights of the PSUs, of the households and all their residents, and of the selected residents. The weights of the PSUs considered the probability of selection of these units for the main sample and the research sample.

In the descriptive analyses, we reported the weighted frequency of disease-associated activity loss as a proportion (%) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). In the hypothesis’s tests, we utilized binary logistic regression models to assess the relationship between the healthy lifestyle scores (“predictor”) and presence of headache-associated activity loss (outcome). Separate logistic regression models estimated the associations between each one of the six factors of the healthy lifestyle score and headache-associated activity loss. In these models, each factor was categorized based on the adherence levels low (set as reference), moderate, and high. The results are presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The no activity loss group was set as the reference group.

Crude and adjusted models were fitted to assess the independent effect of the healthy lifestyle score on headache-associated activity loss. The adjusted models controlled for the effect of age, sex, skin color, marital status, educational attainment, household income, housing place, region, and labor force status. All regression models used survey weights to account for unequal selection probabilities, non-response, and post-stratification adjustments.

To identify possible non-linear relationships between the healthy lifestyle scores and headache-associated activity loss that cannot be verified using linear regression models, we modeled these relationships using restricted cubic splines with 4 knots positioned at the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles of healthy lifestyle scores, following Harrell´s method [44]. Reference values for healthy lifestyle scores (0 to 14) were set at 9 points, which was the whole sample´s median value. The regression models built for the cubic splines were also adjusted for age, sex, skin color, marital status, educational attainment, household income, housing place, region, and labor force status.

A type I error rate < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant in all analyses. All analyses were conducted with Stata software (version 17.0, StataCorp LLC). Complex sampling design svy commands with weights for the non-response sample corrections and post-stratification adjustments were performed.