The monks soaked the animal-skin parchments in milk or lemon juice, scraped them with pumice stones and sprinkled them with flour to create a fresh surface for new writing, according to Uwe Bergmann, a visiting professor of X-ray science at SLAC.

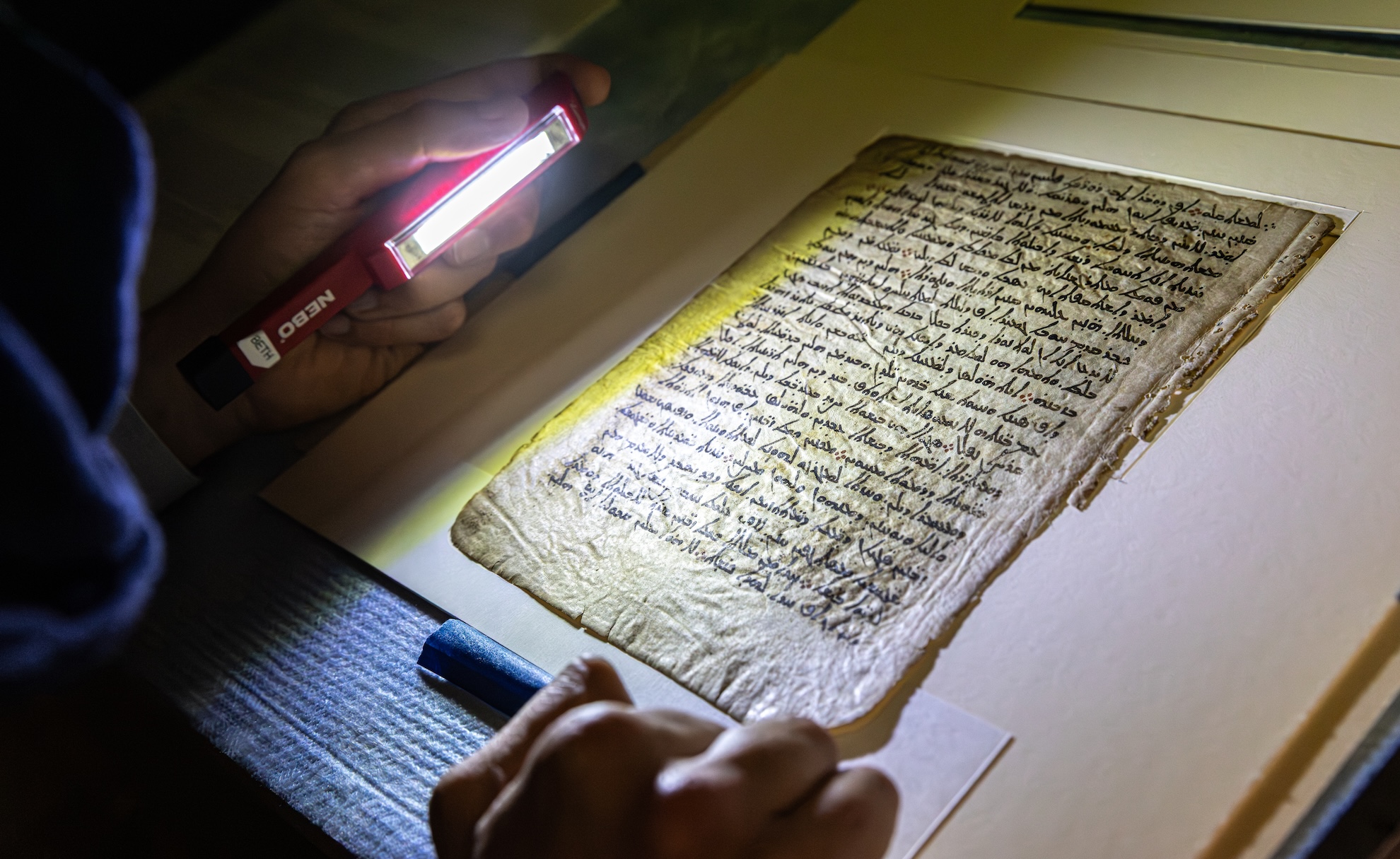

In this case, the original Greek astronomical notes were erased to make way for a Syriac translation of works by St. John Climacus, a 6th-7th century monk. While the religious text is easily visible to the naked eye, the ancient coordinates for the stars and notes on Hipparchus’ work remained a series of invisible smudges for centuries.

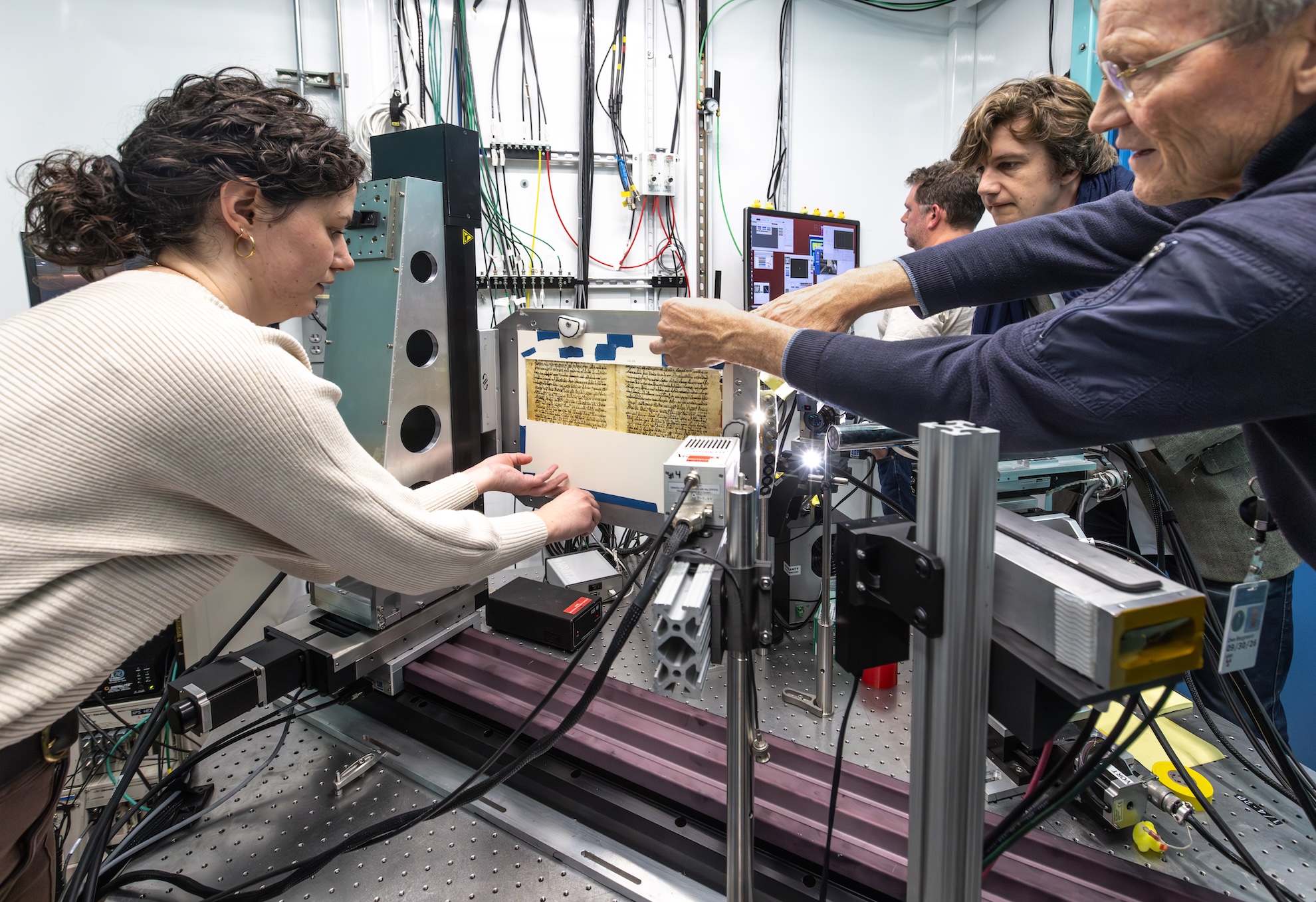

Late Tuesday, the team at SLAC began scanning 11 pages of the manuscript provided by the Museum of the Bible. By Wednesday morning, the monitors were showing line after line of ancient Greek.

The process relies on the specific chemistry of the inks used across different eras, physics Ph.D. student Minhal Gardezi said. The top layer of ink used by the monks is rich in iron, while the underlying Greek text contains a strong calcium signal.

By tuning the X-ray beam, researchers can create elemental maps that separate the layers. This allows them to effectively “see” the underlying layer — without the top layer obscuring the view.

By Wednesday morning, the team had already identified the word for “Aquarius” and descriptions of “bright” stars within that constellation, Gysembergh said. The researcher said he’s been waiting four years for this experiment, which followed his earlier publications on the manuscript.

“I am at the peak of my excitement right now … because of this new scan that we started, line after line of text showing up in ancient Greek from the astronomical manuscript,” Gysembergh said.

While multispectral imaging had previously revealed some fragments, the X-ray fluorescence technology at SLAC allows for much higher resolution. Gysembergh and his colleagues can now use these coordinates to answer fundamental questions about how ancient astronomers achieved such high precision without magnifying instruments.

“What the Greeks knew about our world was unbelievable,” Bergmann said. “Knowing about these great thinkers from ancient Greece, going into the most modern advanced science of today, for me, it has become really, really fascinating.”

The technical side of the study is a massive interdisciplinary feat, according to Sam Webb, a lead scientist at SLAC. Webb built the instrumentation and experimental hutch that houses the world’s brightest X-rays.

The process involves a synchrotron, or a particle accelerator, which propels electrons to nearly the speed of light. As these electrons are “wiggled” by magnets, they shed off X-rays that are used to illuminate the manuscript, Bergmann said.

Bergmann said that to ensure the safety of the fragile parchment, each 10-millisecond pulse of X-ray light hits a spot the width of a human hair. Bergmann said the team is careful to keep the “dose” of radiation well below a safe limit, much like a medical X-ray.

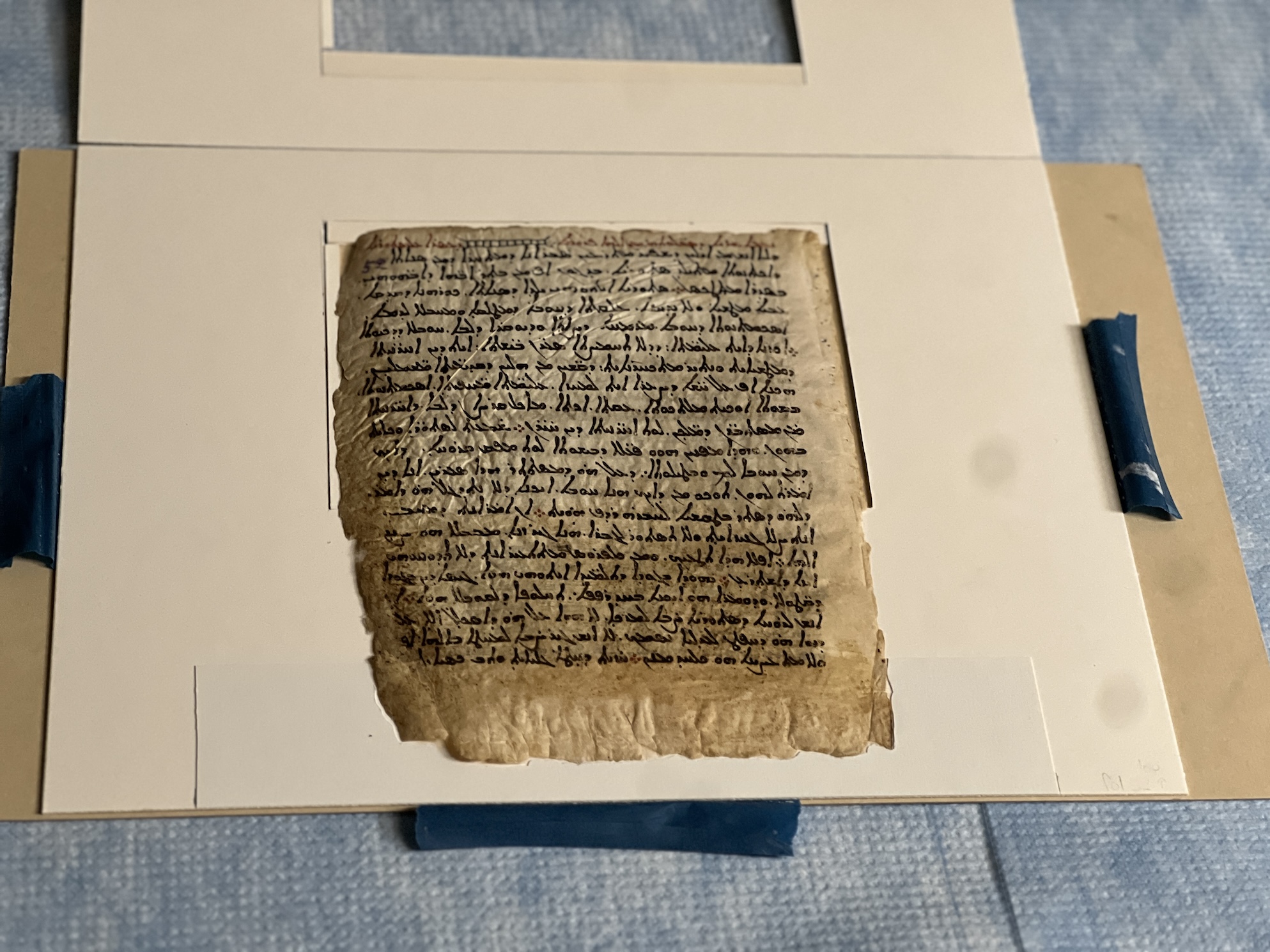

Elizabeth Hayslett, a conservator from the Museum of the Bible, spent weeks preparing the 11 folios for the journey. The pages traveled in humidity-controlled cases under a strict hand-carry policy to prevent any damage. During the scanning process, the team keeps the lights low in the experimental hutch to prevent further fading of the ink.

These pages are part of a larger 200-page codex. While this specific set of pages is held in Washington, D.C., other parts of the manuscript are scattered globally.

Beyond the excitement of the hunt, the findings carry significant weight for the history of science. According to Gysembergh, historians debated for years whether the Roman astronomer Ptolemy had plagiarized Hipparchus’ star catalog.

Gysembergh said that by comparing the new data from the SLAC scans with Ptolemy’s preserved records, they can now prove that Ptolemy did not simply copy the work.

“We can show that Ptolemy did indeed sometimes use Hipparchus’ data, but he also used other sources. So, that’s not plagiarism. That’s actual science,” Gysembergh said. “That’s what we still do today to combine data sources to get the best data possible.”

Keith Knox, an imaging scientist with the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library who has worked on similar projects for 30 years, said the goal is to enhance the writing so that scholars can finally read it. Knox previously worked on the famous Archimedes Palimpsest and said that the star-map project is the latest step in a decades-long effort to recover secrets from the past.

“This is just the latest event of working on this one manuscript, trying to recover the secrets of the writing that was erased a long time ago,” Knox said.

Because the X-rays see through both sides of the page simultaneously, Knox and Ph.D. students use advanced data processing to statistically separate the front and back text. On some pages, there may be as many as six layers of ink to untangle.

“If we can show how useful — and how informative — the science can be, the hope is that then more scholars who might have interesting documents, interesting artifacts, would then come to us and we can learn more about those,” chemistry Ph.D. student Sophia Vogelsang said.

The next phase will involve scholars of ancient Greek, who will painstakingly translate the coordinates and descriptions to fully reconstruct the father of astronomy’s lost catalog.