A recent interdisciplinary research is prompting archaeologists to think about why, despite the problematic history, the concept of “culture” remains so pivotal in archaeological studies of the human past. Carried out by archaeologist Johanna Brinkmann and philosopher Vesa Arponen at Kiel University’s ROOTS Cluster of Excellence, this study examines the definition, critique, and persistence of archaeological culture. Their findings have been published in the journal Germania.

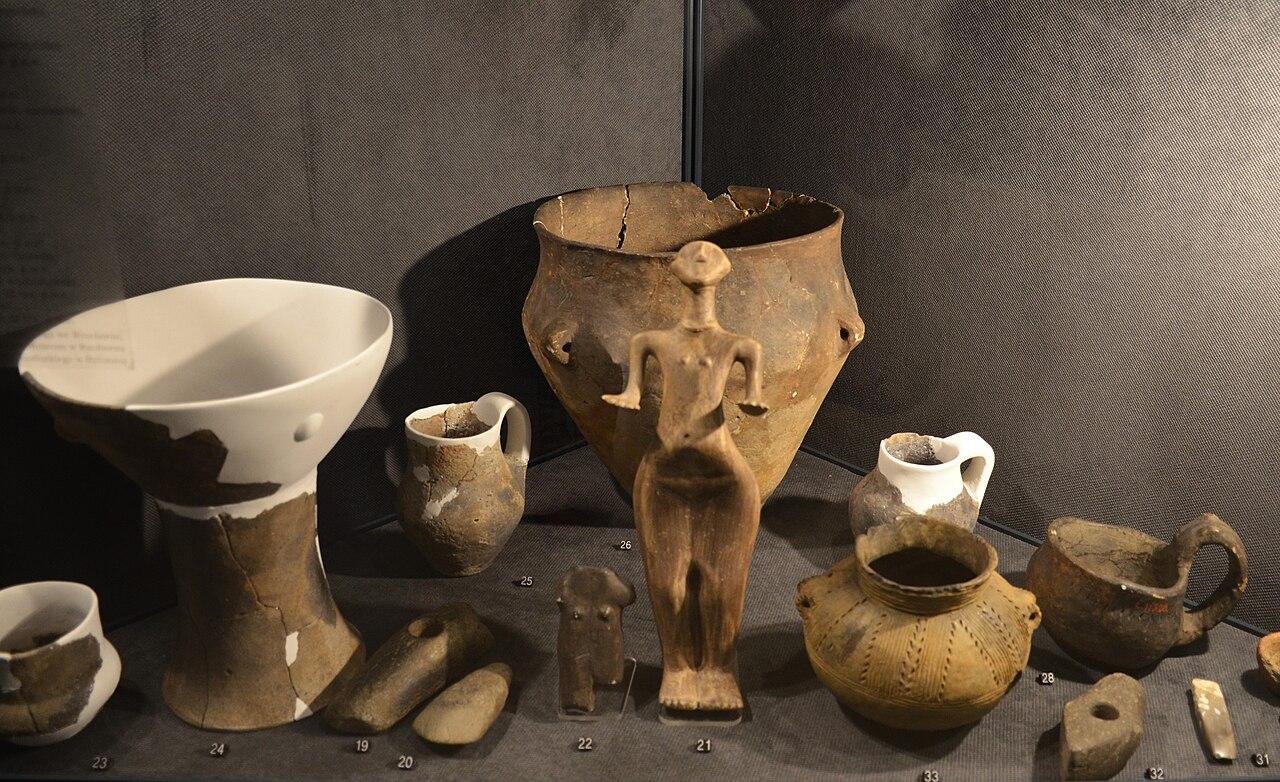

The term “culture” has been extremely problematic within archaeology from the early 20th century onwards, largely due to the work of scholars such as Gustaf Kossinna and other archaeologists who associated material remains directly with racially and ethnically defined peoples. These ideas were later used by Nazi ideology and interpreted in the context of nationalist propaganda. But it was the aftermath of World War II that left many archaeologists uneasy with the use of the word “culture,” and yet the Funnel Beaker Culture is one of the commonly used terms, particularly in European prehistoric studies.

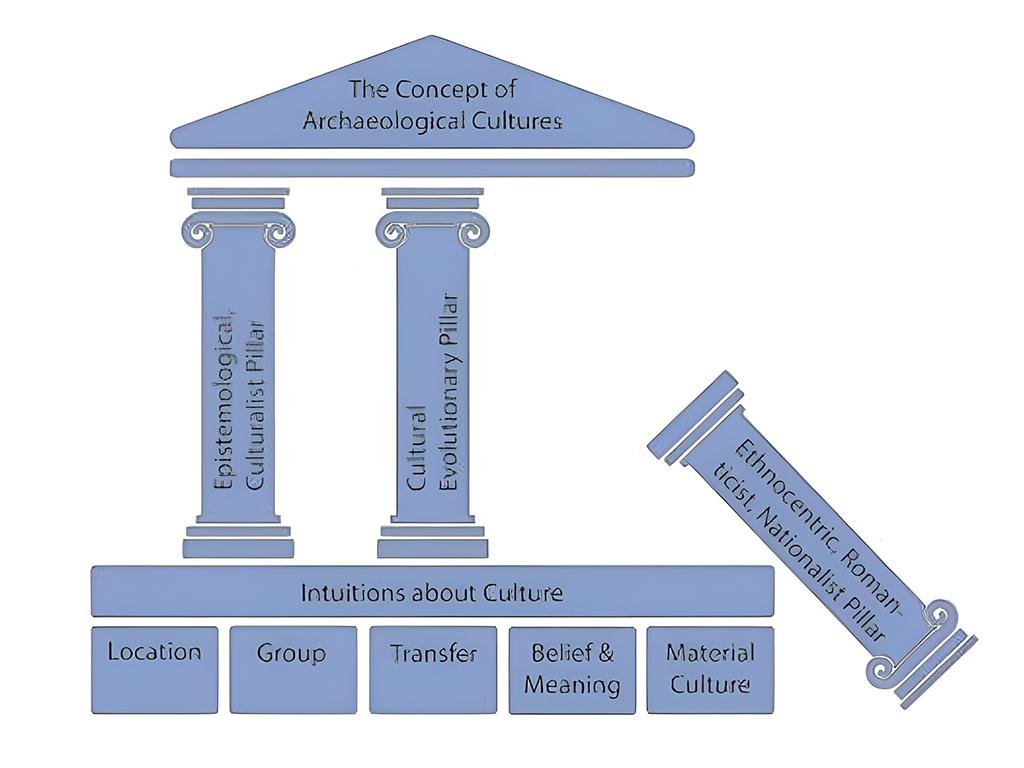

To account for this paradox, the authors suggest that the concept of culture from the archaeological side does not rest on a single theoretical foundation, but stands on three distinct pillars. These are the ethnocentric, romanticist, and nationalist approaches associated with Kossinna, which the authors regard as scientifically untenable and largely rejected today, but two other pillars continue to shape archaeological thinking.

One of these is a cultural-evolutionary approach, which sees culture as a dynamic process in which skills, knowledge, technologies, and ideas are passed down from one generation to another. The second is a culturalist approach, which tends to be more skeptical about universal or environmentally deterministic explanations and emphasizes the uniqueness of cultural forms, ideas, and practices within specific communities. Both these perspectives are vastly different from each other, but both are useful in explaining why “culture” as a concept has survived the collapse of its most questionable foundation.

Five core intuitions are also identified in the study that consistently underpin how archaeologists think about culture. These include association with specific locations, the existence of social groups, the transfer of practices and ideas through time, material culture, and shared beliefs and meanings. Although these elements were originally part of the early culture-historical thinking model, they have persisted in modified forms within the cultural-evolutionary and culturalist frameworks. This continuity helps clarify why archaeologists continue to rely on cultural classifications, despite the historical risks.

However, beyond theory, the authors go on to argue about the practical challenges in archaeology, such as the need to classify large amounts of material evidence. There may be alternative models for classification, such as polythetic classification, that offer flexible and reflective approaches, but they are often complex to apply. Ultimately, the authors conclude that it is not enough to simply reject the nationalist roots of the culture concept. Because its core intuitions remain embedded in modern approaches, careful reflection is required, especially as new methods, such as the analysis of ancient DNA, risk reviving older ideas about peoples and origins.