OU Police Department Chief Nate Tarver first met Johnny Lee Clary outside Moore High School in 1980. Tarver, the first and only Black police officer in the city at the time, was in uniform, while Clary was in his Ku Klux Klan robe and hood.

The KKK was rallying at Moore High School to recruit students, and Tarver was the first to arrive on scene. As Klan members took up the area next to the street in front of the school, many students were angry they were there and threw balls of dirt and pebbles at them.

“Well, Nate, what are you going to do about this?” Tarver’s supervisor, Lt. Leighton Stanley, had asked.

Tarver told him the Klan had the right to be on that property, so it was the students who were wrong to harass them — his answer was legally right if personally challenging. Officers got the students under control and the Klan eventually left, but Tarver would meet Clary again soon.

Tarver will retire this month after 46 years in law enforcement, a field he said gave him the opportunity and purpose to show compassion and respect to people in the community.

“When people are treating you badly, calling you names, spitting on you, cursing you, I know what it feels like,” Tarver said. “I know what it feels like, and I don’t want to ever make another human feel that way.”

‘Someone that looked like me’

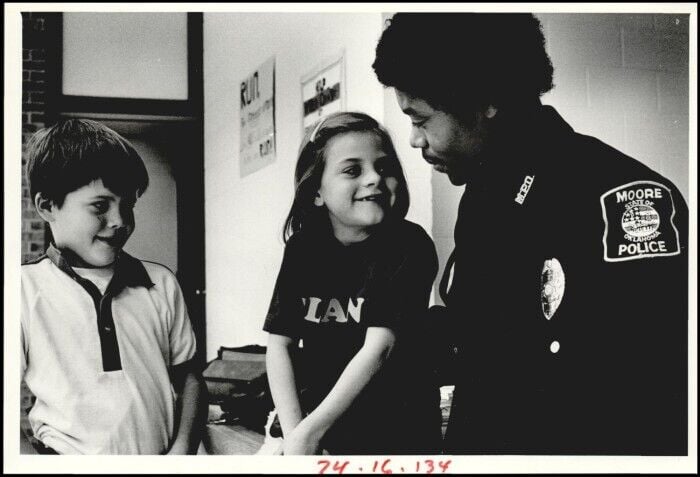

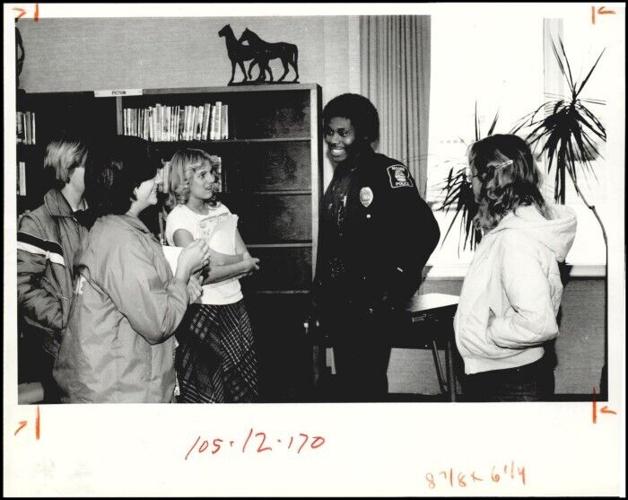

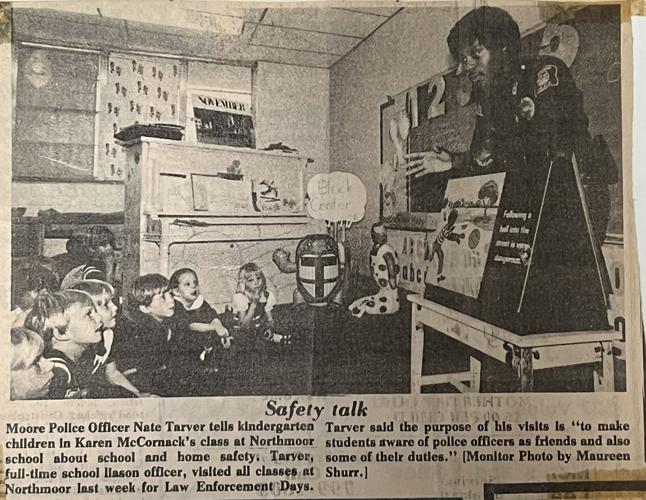

Tarver, a Tulsa native, graduated from OU in 1978 with a degree in broadcast journalism, but couldn’t find a reporting job. While paying his utility bill at Moore city hall, he saw an advertisement posting to hire police officers. He’d never considered working in law enforcement, but he needed a job.

The Moore Police Department hired Tarver in 1979, though he said the staff onboarding him tried to find anything in his past that would eliminate him. Tarver said he had to take three polygraph tests to prove his record was clean.

Tarver believes it was the Moore police chief at the time who decided to give him a chance.

“It was something that I wanted to try. Once I got it, I found out that I really, really liked the job,” Tarver said. “I really liked what it stood for as an opportunity to help people and to make some change.”

Most Moore residents were accepting and curious about Tarver, but there were officers and some residents who didn’t want him there. He said residents would call him names, slam doors in his face and report stolen police cars because they couldn’t believe a Black man was allowed to drive one.

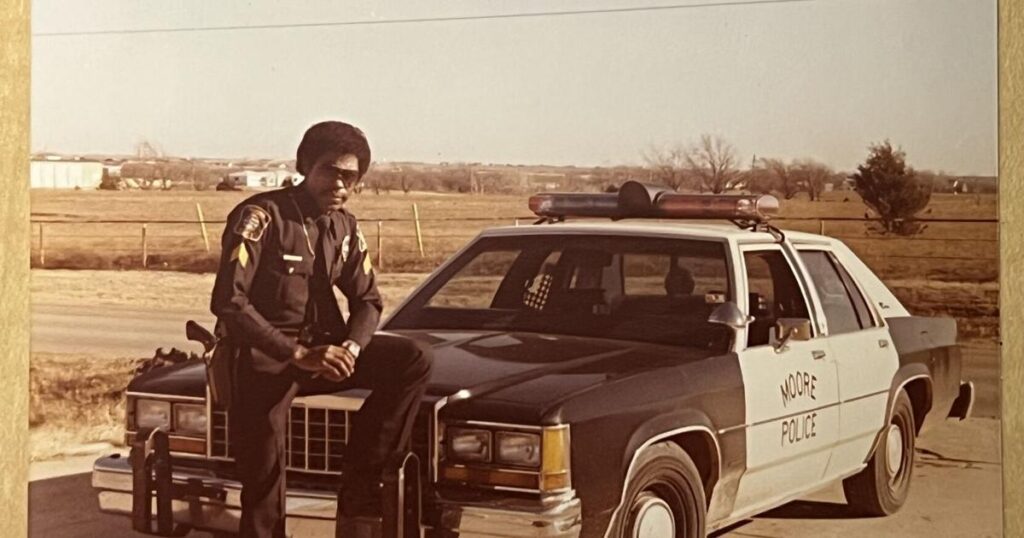

Nate Tarver in front of a Moore Police Department car.

“They just couldn’t believe that someone who looked like me would be in a police uniform,” Tarver said.

The KKK rally at Moore High School happened about a year into Tarver’s tenure at the Moore Police Department. After the rally, Tarver continued to see Clary around town. Tarver would greet him, but Clary would only stare back.

A few years later, Clary got into a fight with another KKK member. Tarver was again the first to arrive on scene.

When Tarver found Clary, he had been hit over the head with a shotgun, his head cut open and bleeding. Tarver wrapped a towel around his head and attended to his wound until medical help arrived. When police arrested the man who assaulted Clary, Tarver testified in court on Clary’s behalf.

“(Clary) said, ‘I can’t believe you testified on my behalf,’ and of course, I said, ‘Well, you know, that’s my job,’” Tarver said. “He thanked me and he said that he was going to have to reevaluate his thoughts regarding the Klan.”

People call the police in their worst moments, Tarver said, so officers must be compassionate and helpful. Driven by his faith in God, Tarver said he believes each person has value and his faith gives him the strength to treat them as such — even if they don’t respect him in return.

Tarver also had conversations with Moore officers and residents about their misconceptions about Black people. Even when they disagreed with him, he said people have a “right to be wrong.” He said some conversations were tough, but they helped others understand Tarver’s experience.

“It was an opportunity to teach people that you can’t judge someone just based on their appearance or how they talk or what your preconceived notions are,” Tarver said. “I was very successful at that. I actually got a lot of people to change their minds.”

‘Overcome your fear’

After 10 years at the Moore police department, Tarver moved to the Oklahoma City Police Department in 1989. He said he’s seen much suffering, including tornado damage, deaths and homelessness. But Tarver said nothing compared to witnessing the destruction of terrorism: the Oklahoma City Bombing.

“The carnage and the people, … when I walked around to that building and saw that, I felt like, for a moment or two … I just stood there with my mouth hanging open and just couldn’t believe what I saw,” Tarver said. “I’m sure it wasn’t that long, but it just seemed like it, because it was a shock to the system.”

Tarver said God protected him throughout his career as he remembered bullets whizzing past his head, seeing tragic deaths and witnessing other dangerous situations that left him physically unscathed. Tarver said he has never killed anyone or been hospitalized with a work-related injury.

Nate Tarver with several Oklahoma City metro police chiefs in front of the Oklahoma City Police Department headquarters.

Still, mental health is a struggle for many officers, Tarver said, and improving their mental health helps protect them from the suffering they’ve seen — things most people will never witness.

Last year, Tarver said he saw a little girl’s clothes catch fire while she roasted a s’more at a football game. He helped put the fire out and the girl was fine.

But Tarver wasn’t fine. He said the incident brought him back 10 years to a wrecked car engulfed in flames on Hefner Parkway. The fire was so intense Tarver couldn’t help the man trapped inside.

“(The) feeling of helplessness, that’s one of the worst things for police officers,” Tarver said. “To feel like there’s nothing you can do, because there wasn’t anything I (could) do, I couldn’t get close enough to it because of the fire. I watched this guy burn to death.”

Tarver has since been cleared by a counselor, but he said it’s important to talk about mental health. At the beginning of his career, he said officers wouldn’t talk about their problems because they believed it showed weakness, but all it did was make the issue worse.

People ask Tarver if he ever feels afraid. He said he does, but his sense of duty motivates him to push past it. He said he’s honored to be the person who runs into danger because not everyone can.

“Police officers have to kick it in gear, and you have to overcome your fear. You have to overcome your trepidation to get the job done,” Tarver said. “That’s why it’s a calling.”

In 2015, Tarver became the deputy chief of police for the OU Health campus police department. He was promoted to chief in 2017.

Nate Tarver in front of OU Police Department headquarters.

In 2020, OU administration decided to unite its three police departments — previously separated by the Norman, Health and Tulsa campuses — under one department and one chief. Eric Conrad, OU’s chief operating officer at the time, wanted Tarver to take the job but Tarver declined.

After a failed national search, Conrad returned to Tarver. Tarver said Conrad pleaded with him, and Conrad’s faith in Tarver’s abilities changed his mind. Although the challenges of campus policing made him nervous, he said yes.

As chief, Tarver prioritized talking with athletes, students in greek life and student government members to hear their concerns and be a familiar face. He said he feels the weight of parents trusting him with their kids’ safety.

Tarver said he’s in the business of education — the university can’t function without students, but parents won’t send their children to school if they’re afraid for their safety.

“We want them to come to the University of Oklahoma,” Tarver said. “I’m in the education business, all right, because there’s no education without students.”

‘We want to change too’

Tarver stepped into the role of chief in September 2020, a few months after George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis and while the Black Lives Matter movement was underway.

At the time, many OUPD officers quit and recruitment numbers were decreasing. Tarver said the department was operating with only 25 officers, down from approximately 40. Tarver ensured officers were trained in human rights protection and de-escalation as they worked campus protests.

Tarver also told his officers they must be a part of the community and hold its values; they needed to listen to concerns about police aggression, because residents would only allow policing as much as they want to, he said.

Tarver said 2020 revived necessary conversations about race and policing. He believes his experience in Moore prepared him for it.

“After dealing and living through the things I’ve lived through in the early part of my career, I didn’t sweat a lot of that stuff because I was already ready,” Tarver said. “I was built to hear those conversations. I was built to have those conversations and talk to people.”

Tarver spoke with Black officers in other cities and addressed multiple questions from Black students in greek life.

“We hear you and we understand what you’re saying, and we want to change too,” Tarver said. “That’s why we got in this business. We want to affect change from the inside.”

David Surratt, vice president for Student Affairs and dean of students, said conversations he had with Tarver in 2020 were frank and meaningful as they worked together to deal with social issues on campus. As a minority in a leadership position at OU, Surratt said he related to Tarver in ways few others understood.

“It’s a special moment in history that takes remarkable people to stay committed to that work,” Surratt said. “It was even more difficult then, in managing all the pressures.”

Surratt said Tarver is a calm, strong communicator and a steady leader, with a unique focus on student and community engagement. Surratt said Tarver’s support in difficult situations made him feel seen and encouraged.

OU Health campus Deputy Chief Terry Schofield said Tarver is genuine in all his actions and words, and a generous person who makes time for others. Schofield said Tarver works tirelessly to keep every student, faculty member and staff member safe.

Tarver is always willing to give people a chance, Schofield said, because many people have taken chances on him in his career.

“The way he kind of explained it is, ‘When God opens a door for you, you better be smart enough to walk through,’” Schofield said. “And then that’s what he did.”

OU’s Norman campus Deputy Chief Kent Ray said Tarver is a man of character who generously pays for people’s meals, volunteers with the Engaging Men group for the Oklahoma City YWCA and makes time to listen to all people. Ray said Tarver leads by example in being out in the field with officers.

“He always saw everybody as valuable, contributing individuals, and he always treated people good,” Ray said. “There are a lot of people out there that will look down on a person doing a certain type of job. And he was one of those who would always respect people no matter what their station was in life, what their position was, what their financial situation was, what their mental situation was … What else can you ask for a person?”

Tarver also served in the Navy Reserves for seven years, is a member of the Oklahoma Law Enforcement Hall of Fame and is a distinguished alum of the Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication. Once he retires, Tarver plans to travel with his wife and spend time with his three daughters.

Black officers in Moore still reach out and thank Tarver for paving the way for them. However, Tarver believes he gets more praise than he deserves.

“I was just doing what I needed to do to get through to survive and be positive about it,” Tarver said.

Years after Tarver last saw Clary, he received a letter from him. Clary had renounced the KKK and was now an ordained minister in a Black church.

“I know there are Black people that are good people, because I’ve met them, and you’re one of them and you were always kind to me,” Tarver said Clary wrote to him. “You always treated me with respect.”

This story was edited by Ana Barboza, Thomas Pablo and Natalie Armour. Larkin Bock, Ryan Little, Chelsea Low and Gretchen Schultz copy edited this story.