Bea SwallowWest of England

Handout

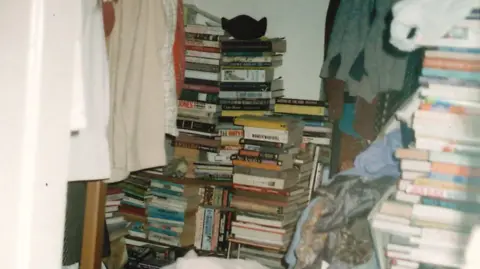

HandoutA sliver of space left on a mattress, narrow winding pathways carved through clutter and precarious piles of newspapers – this is just a small glimpse behind the curtain of a person living with a hoarding disorder.

Jess, not her real name, navigated a turbulent childhood which she said manifested itself in adulthood as a “paralyzing anxiety” when faced with difficult situations.

“I feel my environment has always been out of control and that’s part of the problem,” she explained. “It’s an inability to deal with things.”

Jess, who lives in north Bristol, said her problem with clutter began innocently through accumulating books in a bid to become more “self-reliant” after moving to university to escape her difficult home life.

As the years passed her collection morphed into a hoard that was too “overwhelming” to face – every room in her flat overflowing with boxes of paperwork, food, packaging and clothing.

On one occasion, her parents turned up unannounced on the doorstep for a surprise visit but she could not bear to let them in.

“I felt absolutely dreadful, I was so embarrassed” she said. “In that moment, I felt the pain of not being able to be who I wanted to be.”

Jess, who is in her 70s, goes into “panic mode” when the doorbell rings and will not allow anyone into her home due to fear of shame and judgement.

She described the “terror” of making new friends in case they might expect their invite to be reciprocated and chooses her words carefully to avoid exposing the “chaos” she calls home.

“It’s an extremely distressing and limiting condition,” she explained. “It has such a massive impact on every aspect of my life.

“Somebody coming in from the outside, who doesn’t have an understanding, might think we’re lazy, unclean or greedy.

“But it’s not a lifestyle choice, it’s a mental health issue.”

What is hoarding disorder?

Hoarding was recognised as a complex mental health condition in 2013.

Between two and five per cent of the UK population is estimated to be affected by a hoarding disorder – equating to about 1.2 million people.

It is defined as the urge to acquire unusually large amounts of possessions and an inability to get rid of those possessions – even when they have no practical use or monetary value.

According to the NHS, hoarding becomes a significant problem if it negatively affects the person’s quality of life, causes significant distress and interferes with everyday living.

Nosa

NosaJames Hicks, 41, a cognitive behavioural therapist (CBT) at Nosa in Staple Hill, said it often stems from a “heightened emotional attachment” to objects.

“When you look deeper into somebody’s past, quite often you’ll find they were treated less than desirably by the people that were important in their lives,” he said.

“What would it feel like if you had value and meaning but somebody simply dismissed you? Well that would feel awful, wouldn’t it?

“They believe they are responsible for the wellbeing of their belongings and if they discard them, they are doing them a disservice.

“If you felt every time you took the rubbish out you were ripping yourself away from a loved family member then you might have some idea of what it’s like to suffer from hoarding disorder,” he added.

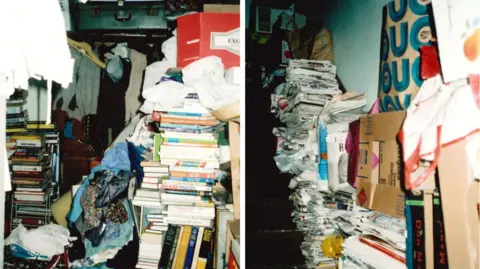

Handout

HandoutHorace, not his real name, also has a hoarding disorder.

He said this “sense of loss” originated when his father threw away his collection of 1920’s records as a teenager without consulting him.

“I was absolutely gutted, really angry and upset,” he recalled. “It was a question of him imposing his will on me. In the back of my mind that has stuck with me.

“Whether that became a trigger to keep things and make sure nobody disposed of them, I don’t know, but I suspect it probably was.”

‘Mini bereavement’

An inherent “thirst for knowledge” eventually led to Horace stockpiling books and newspapers with the intention of cutting out interesting excerpts later.

He would even dig through neighbours’ recycling boxes because the thought of wasting valuable information was unbearable.

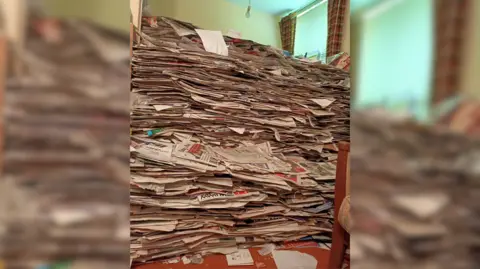

“I had a mountain of newspapers, almost as tall as I was, blocking my hallway and staircase,” he said.

“I would have to clamber over it to get to any other room. Bags and bags of books and newspapers stacked on top of each other that I’d collected over 20 years.

“It’s ridiculous to think I got myself into that situation, but I did.”

Horace said he had drastically reduced his hoard over time but described getting rid of his things as a “mini bereavement”, watching items he once loved disappear, knowing he will never see them again.

Making Space

Making SpaceThe pair have since joined a charity group called Making Space, funded by Bristol City Council, which helps provide practical and emotional support for those with the condition.

Volunteers receive training on how to work on a one-to-one basis with tenants and must be able to give two hours of their time a week.

Case manager Naomi Morgan described the “hugely rewarding” role as an “integral part of transforming people’s lives” by increasing their confidence and wellbeing.

Jess said the tailored experience has not only helped her clear space but “make a home”, and now looks forward to “a more sociable and less anxiety-ridden future”.

‘Untangling the origins’

Jess now possesses a better understanding of what causes her hoarding tendencies, but says “it has been a long journey”.

“It’s really hard for people with hoarding disorder to understand why they’re doing the things they’re doing, why they’re living this way,” she explained.

“It doesn’t make any sense, and it’s hard to untangle those origins.”

Horace urged people to treat those with the disorder with “kindness, patience, respect and empathy”, and allow the person to remain in control.

“Even if you can’t understand it, don’t be judgemental,” he pleaded.

“Try to support them by encouraging them, rather than simply saying ‘this is no way to live’.”