Today, I want to tell you about a woman whose stories changed how the world understood an entire nation. She did it not out of duty, but out of a more dangerous impulse: love.

Her name was Anita Brenner. She was Mexican-American. She was Jewish. And she was absolutely convinced that the world had Mexico completely wrong.

Anita Brenner was born in 1905, in Aguascalientes, Mexico, to a problem that would define her life: she belonged nowhere. In a deeply Catholic community obsessed with indigenous roots and unmistakably Mexican surnames, the Jewish girl with the hyphenated identity was a foreigner in her own birthplace.

That hunger to understand the place that rejected her became her superpower. While other people might have simply left and never looked back, Brenner decided to become an expert on the thing that had cast her out. From childhood, she wielded the only real tool available to women of her era — her pen.

By the 1920s, with an anthropology degree in hand, she started writing for The Jewish Daily Forward in New York, winning contests with essays that were decades ahead of their time in intellectual dexterity and emotional honesty. Then she did something audacious: she infiltrated Mexico’s artistic and political circles with such thoroughness that a Mexican saying about people who “get into everything like humidity” might have been invented for her.

Between 1924 and 1925, she formalized her position as correspondent for B’nai B’rith International, a Jewish nonprofit organization in Mexico, crafting a narrative that would later reshape how the world perceived Mexico. In the chaos of the post-Revolutionary era, when Europe was turning inward, she portrayed Mexico as a sanctuary — a modern country, safe, sophisticated, and worth looking at.

The first time Mexico became cool

There was a cultural phenomenon in the early twentieth century that we rarely talk about with the excitement it deserves. Mexican artists, writers, and intellectuals flooded New York and other American cities.

Anita Brenner was the architect of this paradigm shift, writing for the magazines that mattered — Mexican Folkways, The Nation and Mademoiselle — and she did something radical: she refused to treat Mexican culture as a distant third-world curiosity. She presented it as a vanguard. She was among the first to describe what art historians now call “the Mexican Renaissance” — the moment when Mexican artists looked to indigenous civilizations the way Renaissance masters had gazed at Roman ruins and created something entirely new. She helped place Mexican muralists in galleries and museums across America. She was the translator who made the incomprehensible suddenly inevitable.

The intellectual circles of New York were electrified.

Idols Behind Altars

In 1929, Anita Brenner published what would become one of the foundational texts in Mexican art history: “Idols Behind Altars.” The book marked the moment when Mexican art historiography became international.

The book did something almost no one had done before: it treated Mexican culture as a unified continuum. Pre-Hispanic art. Colonial art. Popular art. Modern art. Muralism. Not as separate categories, but as chapters in a singular, thousand-year conversation about what it meant to be Mexico. A retablo hanging in someone’s home had the same scholarly weight as a mural by Diego Rivera. Ceramics were studied with the same rigor as oil paintings. Brenner refused the distinction between high art and low art because she understood that this distinction was itself a form of erasure.

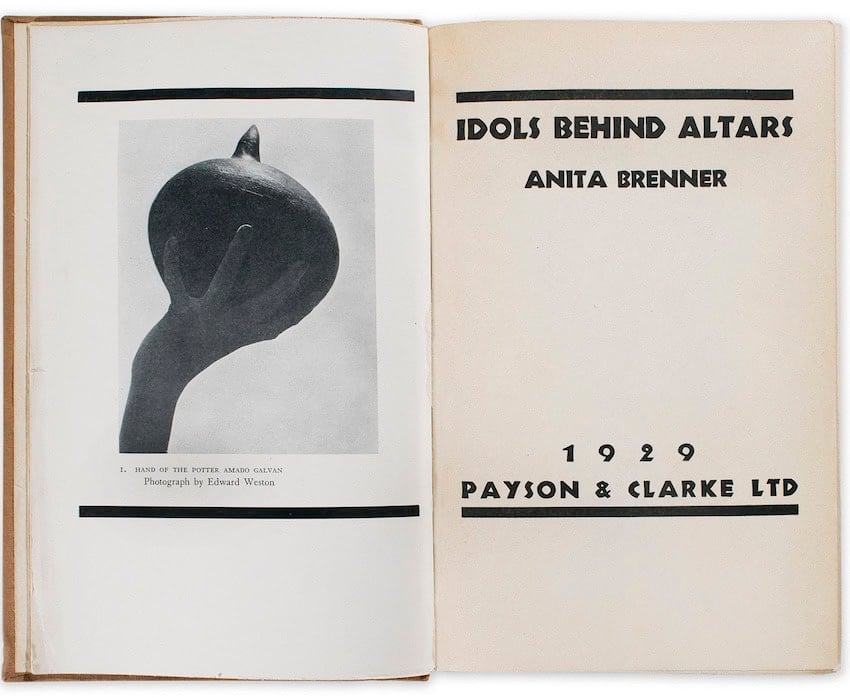

The photography in the book was by Edward Weston and Tina Modotti — two foreigners whose images documented a vision of a Mexico that has transformed almost beyond recognition in the century since.

In her magnum opus, Brenner argued that Mexico was not a nation of violent primitives, but a country with millennia-deep roots and a thriving present. That its strength came from this very continuity — from the past still alive in the countryside, from the colonial period’s productive collision with indigenous traditions, from the modern world’s experiments in radical new forms. In short: that Mexico had a story worth hearing, told by someone who knew how to make the world listen.

New York’s intellectual establishment listened.

The machinery of influence

At the legendary Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), an unprecedented decision was made: for the only time in the museum’s history, they dedicated the entire building to a single exhibition. Entitled “20 Centuries of Mexican Art,” the accompanying catalogue followed the exact intellectual architecture of Brenner’s book, although her name was never credited directly.

This growing American fascination with Mexico triggered investment and tourism. It reshaped how American capital flowed into the country. The machinery was complex and multilayered, involving diplomats like Dwight W. Morrow (J.P. Morgan’s partner) and power brokers like Nelson Rockefeller, all with their own strategic interests in presenting Mexico as modern, peaceful, cultured and crucially, safe for American investment. It involved art, yes. But it also involved finance and influence and the careful construction of narratives that served very specific geopolitical purposes.

Brenner was a crucial part of this machinery, whether she fully understood it or not.

A complicated relationship

But here’s where the story darkens.

In 1943, Brenner published “The Wind That Swept Mexico: The History of the Mexican Revolution 1910–1942,” an illustrated history meant for English speakers just beginning to process what the Revolution had actually meant. It was one of the first comprehensive histories written, a book that seemed to continue the project she’d begun in Idols Behind Altars.

Except it didn’t. It did something far more troubling.

Using photographs from the Casasola archive — many of them posed, many of them unreliable as historical documents — Brenner attempted to construct a visual narrative of the Revolution as progress. The problem, for historians, is this: while her text offered an interpretation at a moment when even Mexican scholars were still trying to make sense of the armed conflict, she romanticized it. She presented the Revolution as the necessary crucible that forged modern Mexico, conveniently eliding what that crucible actually destroyed.

She didn’t write about the food crises it created, the women violated in its chaos, or the colonial art stolen and destroyed. She certainly didn’t grapple with the political complexity — the competing groups, each convinced they alone could save the nation, each willing to massacre villages to prove it. Instead, she presented Mexico’s bloodiest decade as a necessary price for progress, a tragic but acceptable cost of becoming modern.

In doing so, she contradicted everything she’d argued just fourteen years earlier in, when she’d insisted on the dignity and continuity of Mexican culture. The Revolution, in her first book, was a rupture to be understood. In her second book, it was a rupture to be celebrated.

A changing tale

Why did Anita Brenner change her story? The answer lies in understanding the specific moment she was writing in.

The interwar period was a time of urgent strategic concern for American power. After the Revolution, Mexico had a problem: it was perceived abroad as wealthy in resources but unstable in society — a country that had just exploded into civil war, and that was now flirting with socialism and communism. American businesses needed to invest in Mexican infrastructure, but first, American capital needed to feel safe.

The new Mexican State understood this too. Ambassadors and billionaires and cultural entrepreneurs all realized the same thing simultaneously: Mexico needed a new image. Not a false image, but an authentic one, which was carefully curated. Modern and traditional at once. Cultured and economically sound. An investment opportunity dressed in indigenous beauty.

Brenner’s work was not operating in a vacuum. It was part of an architecture of influence that linked finance, diplomacy, philanthropy, and propaganda into a single coherent machine. The people who wanted to remake Mexico’s image in the American imagination had the resources to make it happen. And Brenner, brilliant, well-placed, influential as she was, became an essential part of how that happened.

Did she understand this fully? We can’t know. Her love for Mexico, her genuine scholarly passion, her binational perspective — all of it became instrumentalized by forces far larger than her individual intentions.

What endures

If you can find Idols Behind Altars, read it. Read it knowing that some sections have been updated by contemporary scholars, that the book reflects the ideologies of 1929, that it was written by a binational woman determined to travel throughout an entire country to make it intelligible to strangers. Read it as a document of a moment that tells us as much about what we valued then as what we value now.

You’ll notice something unsettling: ideas Brenner articulated in 1929 still echo in how we talk about Mexico today. Some have endured because they’re true.

But here’s the deeper lesson: Anita Brenner became an expert in Mexican culture because she refused to accept that her outsider status disqualified her from understanding. She traveled. She studied. She thought carefully. She wrote persuasively. She didn’t know whose ears she’d reach or what impact her work would have—and then it turned out she reached everyone who mattered.

If you’re interested in becoming an expert in anything, you never know what kind of influence you might wield, what doors your knowledge might open, or whose interests — noble or otherwise — your work might serve. That’s not a reason to stop studying. It’s a reason to study more carefully, more critically, and with eyes wide open to the complex machinery that surrounds even the most sincere acts of love.

Maria Meléndez is an influencer with half a degree in journalism.