When Lodi mom Lisa McBride decided to seek out special education services for her son, the process wasn’t too difficult for her. But that’s because she has a bachelor’s degree in child development, worked as a general education teacher for 32 years and is certified as a special education advocate — knowledge and skills most parents don’t have.

“Special education has its own set of acronyms, and its own language, and that is very, very challenging for any parent to access,” McBride said. “They’re stressed and scared and they’re hearing data and numbers and things about their child that they don’t fully understand.”

Shortly after moving to Lodi in 2020, McBride began helping area parents seeking specialized learning plans for their children navigate the Lodi Unified School District’s special education system through workshops and one-on-one meetings.

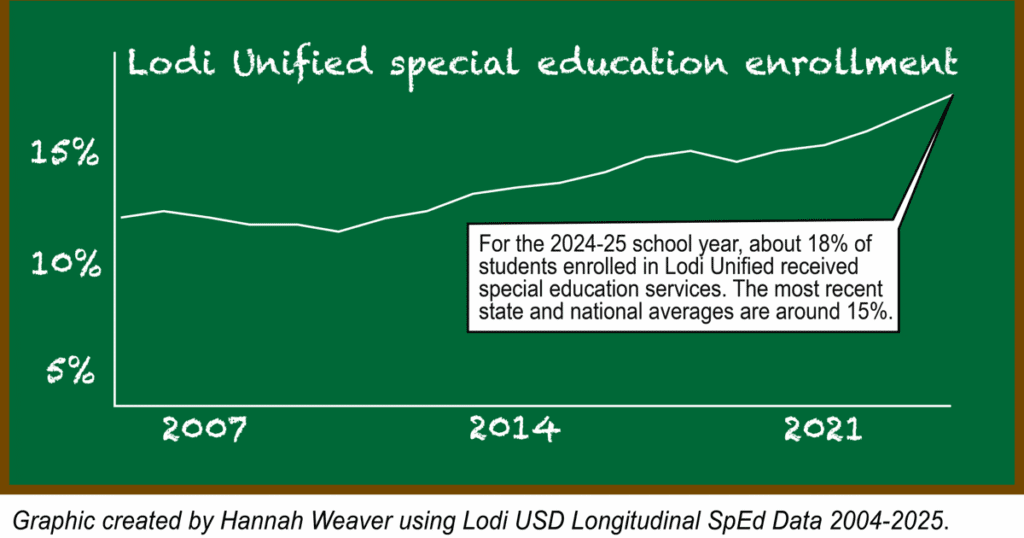

Her services are particularly needed as more Lodi Unified students have been enrolled in special ed programs, which aim to help students who have a disability that affects their learning. The state and national special education enrollment rates have also risen in the past decade, though at a slower rate. As of last school year, roughly 18% of all Lodi Unified students are enrolled in special education — a level several percentage points above the statewide average.

That figure, revealed in a report at an August school board meeting, surprised some parents, educators and even district officials. The report was conducted at the request of school board member and parent Victoria Lenderman, who ran for school board due to her frustrations with the special education system.

The report findings sparked much conversation and debate among meeting attendees and social media commenters. Many speculated about the causes of the higher enrollment rate, suggesting such causes as food preservatives and vaccinations, the latter of which has been thoroughly disproven. Others said the district’s focus should be on providing better services and staffing.

This story is the first in a series of articles the News-Sentinel plans to publish to help readers better understand Lodi’s special education system and the challenges facing students, parents, educators and district staff. If you are part of one of those groups and would like to share your experience for future coverage, please send an email to hannahw@lodinews.com.

First, it’s helpful to know the difference between Lodi Unified and the Lodi SELPA, or Special Education Local Plan Areas. The state is broken into 136 SELPAs, with many made up of multiple districts. San Joaquin County has three SELPAs, including one for the Lodi area. The Lodi SELPA manages special education services for Lodi Unified and three other schools outside the district.

The Lodi SELPA has a Community Advisory Committee, a group made up of parents and educators that meets every three months. Meeting discussion topics have included the basics of Individualized Education Plans (IEPs), the learning plans designed for each student, and the district’s new dyslexia screening process.

Paul Warren, the director of Lodi’s SELPA, prepared and presented the report on special education at the August school board meeting. He works closely with Erin Aitken, director of special education at Lodi Unified. Aitken is a former special education teacher and said her role is more focused on day-to-day logistics like staffing and IEP compliance. Warren’s role is above hers, she said, and also involves overseeing child welfare and attendance. Warren described his position as “focused on compliance, budgets, curriculum [and] best practices.”

In an interview with the News-Sentinel, Warren acknowledged the difficulty for many who try to understand the special education system and emphasized the challenge that comes with trying to meet each student’s individualized needs.

“It’s hard, because special education is very complicated,” he said. “The continuum of different types of placements and services, they’re so different.”

Warren said he’s concerned the rising enrollment might not be reflective of how many students actually require special education services. He said that perspective comes from his background as a mental health therapist.

“If you give kids things they don’t need, that’s harmful,” he said. “A lot of my decisions is what is ultimately going to be best for kids, even if it’s hard.”

Who is included in special education?

Students are eligible for special education if they have a disability that affects their learning and that can be addressed through specialized services. Of the 13 federally recognized disability categories, the most common for Lodi Unified students last school year was speech or language impairment. Specific learning disability was second most common, a category which includes dyslexia, dysgraphia and dyscalculia.

For the 2024-25 school year, Lodi Unified had 4,697 students enrolled in special education programs, or about 18% of its overall student body. That number is 3.3 percentage points higher than the state average. The district’s special ed enrollment rose slowly over the past two decades, and has grown by 3 percentage points from just before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic to now.

Lodi Unified provides special education services to children starting in infancy and continuing into young adulthood. The Dorothy Mahin Early Intervention Center serves “infants and toddlers with developmental delays or at risk for having a developmental disability and their families” as part of the state’s Early Start program. It’s also home to a preschool assessment team, where children over the age of 3 may receive an IEP.

School districts are federally required to identify and evaluate any students who could qualify for special education, according to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Parents can also request evaluation for their child.

How are assessments made?

After identifying a student’s potential disability, the next step is an evaluation process, which is provided free to the student’s family. A school psychologist is primarily responsible for the assessment, often with the help of a specialist in the child’s suspected disability. According to state law, districts have 15 school days to set up an assessment plan once it’s requested by a parent. The assessment must be completed 60 schools days after that.

If the evaluation concludes that a student meets the criteria to receive services, a team sorts out the details of the student’s IEP, within 30 days of assessment. Those teams include a general education teacher, a special education teacher, school psychologist, a specialist and a parent.

After having helped hundreds of parents through the IEP process, McBride said a pattern she sees is parents feeling overwhelmed by the system.

“The biggest thing that they all need to be reminded about is the fact that they are a member of the IEP team, and they are an expert on their child,” she said.

Warren, the Lodi SELPA director, said he thinks the evaluation process can sometimes be too subjective, and suspects that may be contributing to Lodi’s higher special ed enrollment numbers.

“Where there could be variation [in an evaluation] is how people are interpreting data,” Warren said. “It really is about how they’re interpreting and the recommendations that are coming out of their assessments.”

He added that the district is trying to create more consistent evaluation practices, but did not provide specifics of what that would look like.

What services do students receive?

If a student meets the district’s eligibility criteria, they receive their specialized learning plan, a document that is reviewed and updated each year. Each plan lays out a student’s accommodations, additional services and goals. (Some Lodi students get what’s called a 504 Plan, which provides accommodations but not additional services. Those students are not counted in the special education enrollment numbers.)

Accommodations can vary greatly depending on a student’s unique needs. Examples include additional time to complete classwork, receiving written instructions or sitting near a teacher.

Services also range drastically between students and between schools. The most common services schools in the Lodi SELPA provide are speech and language, specialized education instruction and counseling.

Nearly 60% of special education students at Lodi Unified spend 40% or more of their school day in a general education classroom, according to data from the California Department of Education. Many of those students receive support through what’s called the Resource Specialist Program, which tailors general education curriculum to their specific needs. Special education students that require a more specialized learning environment are placed in the Special Day Class program, which groups students together by specific disability or need level.

The Lodi SELPA projects approximately $99.4 million in funding for the 2025-2026 fiscal year. About 60% of that comes from the schools incorporated in the plan area, 32% is from the state and 7% is from the federal government, according to the spending plan.

84% of this year’s total projected expenditures total goes toward employee salaries and benefits, 14% toward services and operations and the rest toward supplies and miscellaneous expenses.

As special education enrollment increases, so does the cost to the district. About 20% of Lodi Unified’s roughly $500 million overall projected expenditures will go toward special education this school year.

“The attitude of our district is special education is going to cost what it costs,” Warren said. “But it doesn’t mean that there are zero financial implications.”

compare to nearby districts?

The biggest differences between Lodi Unified’s special education enrollment compared to state averages were higher rates of students with intellectual disabilities, speech or language impairments and autism.

Lodi has a higher percentage of special education students than neighboring districts do. According to data on each district’s websites, 15% of students at both Stockton Unified and Elk Grove are in special education programs and 14% in Manteca Unified. Galt Joint Union Elementary district had the closest rate to Lodi, at 17.8% for the 2022-23 school year (but the Galt Joint Union High district rate is much lower, at 13.5%).

Is the special education enrollment increase cause for concern?

Karma Quick-Panwala helps families in northern and central California navigate the special education system through the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund. She said the rise of special education enrollment is not inherently concerning.

She attributed the rise to better parental knowledge about the services available, better diagnostic tools and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The vast amount of social isolation inevitably led to anxiety, depression,” she said. “During the pandemic especially, we may have had many students who had invisible disabilities who weren’t identified.”

Warren also acknowledged the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on special education.

“I think we’re still trying to remediate the effects of COVID,” he said.

In his report in August, Warren stated that another factor for the increase in special education enrollment is an “over-reliance on [special ed] to address general academic or behavioral concerns.”

“It’s the equivalent of giving a kid that doesn’t have any problems with their legs crutches and they stop using their legs,” Warren told the News-Sentinel. “There is the great potential for them to develop atrophy and lose the ability to or rob them of the ability to develop skills that may be challenging at the time, but would ultimately be able to meet those challenges.”

Quick-Panwala disagreed with that statement.

“School districts rarely give students the services they don’t need,” she said. “It’s an indication and a reflection of an opinion that maybe doesn’t understand how many students truly need services in the IEP in order to succeed at school.”

Mother and parental advisor McBride added that getting a child special education services is not an easy way out for parents who want help for their children.

“For the vast majority of us who have special needs children, people need to understand it is 10 times the work to develop and to implement and to maintain an IEP within the school system, than to have a student who goes to general ed class,” she said.

Lodi Unified educators and district staff have cited understaffing of its special education program as a key concern as the number of students grows. But according to Lodi Unified’s report, the only potential understaffing is for a special autism preschool day class.

The Lodi teachers union president, Lisa Lennon Wilkins, said that assessment doesn’t match educators’ experience, who she said feel overwhelmed by growing responsibilities

“I was upset when I saw that,” she said of the report.

Lennon Wilkins also expressed concern with the amount of long-term substitutes and interns working in the district, who are not credentialed teachers and are thus ineligible to serve on an IEP team. She also noted that there are no class size limits for Special Day Classes.

Warren said that long-term subs and interns were not included in the staffing ratio report.

“One of the challenges that we have here is trying to support our teachers and support the quality of instruction in a way that meets the unique needs of each of those types of classrooms and programs,” Warren said.

Just over 10% of students’ IEPs were out of compliance in 2024-25, according to the district’s August report. Warren said a much smaller number were “severely” out of compliance.

IEPs can be out of compliance in a number of ways. Quick-Panwala said it often relates to staffing. If even one part of an IEP isn’t completed, for example if a school psychologist misses one session, it’s considered out of compliance.

“My issue is that there are students whose IEPs aren’t being met,” Lennon Wilkins said. “That puts my teachers in danger.”

Lodi Unified is currently exploring next steps to improve the special education program, Warren said. That includes suggestions from parents and teachers to add instructional curriculum coaches, hire an inclusion coach and develop more general education support. Any changes would take effect next school year at the earliest, he said.

“We’re really just still kind of gathering information and laying the groundwork for how we want to look at this data and how we want to move forward,” Warren said.

Hannah Weaver writes for the Lodi News-Sentinel as a cohort member of the California Local News Fellowship program, a multi-year, state-funded initiative to support and strengthen local news reporting in California.