Antimicrobials – antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals and antiparasitics – are substances widely used to prevent and treat infections in humans, aquaculture, livestock and crop production. Their effectiveness is now in jeopardy because a number of antimicrobial treatments that once worked no longer do so because microorganisms have become resistant to them. Microorganisms that develop resistance to commonly used antimicrobials are referred to as superbugs. UNEP released in 2023 the flagship report Bracing for Superbugs: Strengthening environmental action in the ‘One Health’ response to antimicrobial resistance.

What is antimicrobial resistance (AMR)?

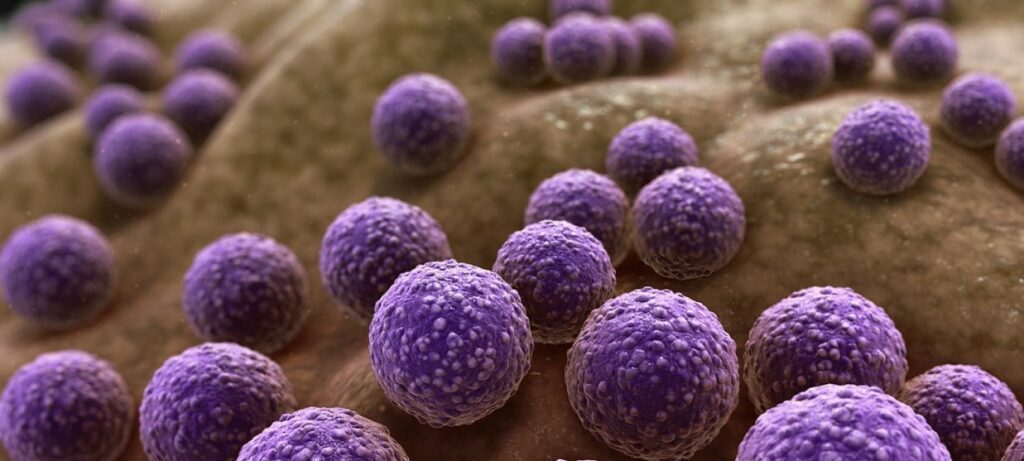

AMR occurs when microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, parasites or fungi become resistant to antimicrobial treatments to which they were previously susceptible.

Increased use and misuse of antimicrobials and other microbial stressors, such as pollution, create favourable conditions for microorganisms to develop resistance both in humans and the environment. Bacteria in water, soil and air, for example, can acquire resistance following contact with resistant microorganisms. Human exposure to AMR in the environment can occur through contact with polluted waters, contaminated food, inhalation of fungal spores, and other pathways that contain antimicrobial resistant microorganisms.

What is the impact of AMR?

The World Health Organization (WHO) lists AMR among the top 10 threats for global health.

Antimicrobial resistance threatens human and animal health and welfare, the environment, food and nutrition security and safety, economic development and equity within societies.

According to recent estimates, in 2019, 1.27 million deaths were directly attributed to drug-resistant infections globally. By 2050, up to 10 million deaths could occur annually.

If unchecked, AMR could shave US $3.4 trillion off GDP annually and push 24 million more people into extreme poverty in the next decade.

Antimicrobial resistance in mycobacterium tuberculosis, malaria parasites, viruses and HIV is becoming a reality that could increase human suffering. It could also deal a huge blow to the world economy, due to productivity losses, increased healthcare costs and a rise in poverty. Even if it is a global crisis, poverty, lack of sanitation and poor hygiene make AMR worse. Also, AMR disproportionately impacts Low-Income Countries and Lower-Middle-Income Countries. AMR is thus an equity issue too.

Management and response to AMR

Environment plays a key role in development, transmission and spread of AMR. Therefore, the response must be based on a One Health approach, recognizing that humans, animals, plants and environment are interconnected and indivisible, at the global, regional and local levels, from all sectors, stakeholders and institutions. Prevention is at the core of the action needed to halt the emergence of AMR and environment is a key part of the solution.

“AMR challenges cannot be understood or addressed separately from the triple planetary crisis – the crisis of climate change, the crisis of nature and biodiversity loss, and the crisis of pollution and waste, all of which are driven by unsustainable consumption and production patterns,” said UNEP Executive Director Inger Andersen.

Three economic sector value chains profoundly influence the development and spread of AMR:

Pharmaceuticals and other chemicals manufacturing.

Agriculture and food including terrestrial animal production, aquaculture, food crops.

Healthcare delivery in hospitals, medical facilities, community healthcare facilities and in pharmacies where a range of chemicals and disinfectants are used.

In addition, poor sanitation, wastewater and related waste effluent in human and animal waste systems, such as municipal wastewater is an important source of AMR.