(SOUTH DAKOTA SEARCHLIGHT) NORRIS — As the last round of students filters in from the school van to the main hallway, Principal Brian Brown greets each student by name, with a high five and an “I’ve been waiting for you all morning.”

After students arrive, they’re served breakfast, and Brown leads a boys’ group and girls’ group in singing Lakota songs to get the day started.

This is the morning routine at Norris Elementary, part of the White River School District in rural southwestern South Dakota. The school borders the Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations, and serves about 50 students from kindergarten through fifth grade who are predominantly Native American.

Norris is an unincorporated community in Mellette County, one of the most impoverished counties in the state. About a third of the students are raised by their grandparents, Brown said.

“We’ve still got kids that live in houses with no running water,” he said. “So, we have our struggles, we have our hardships.”

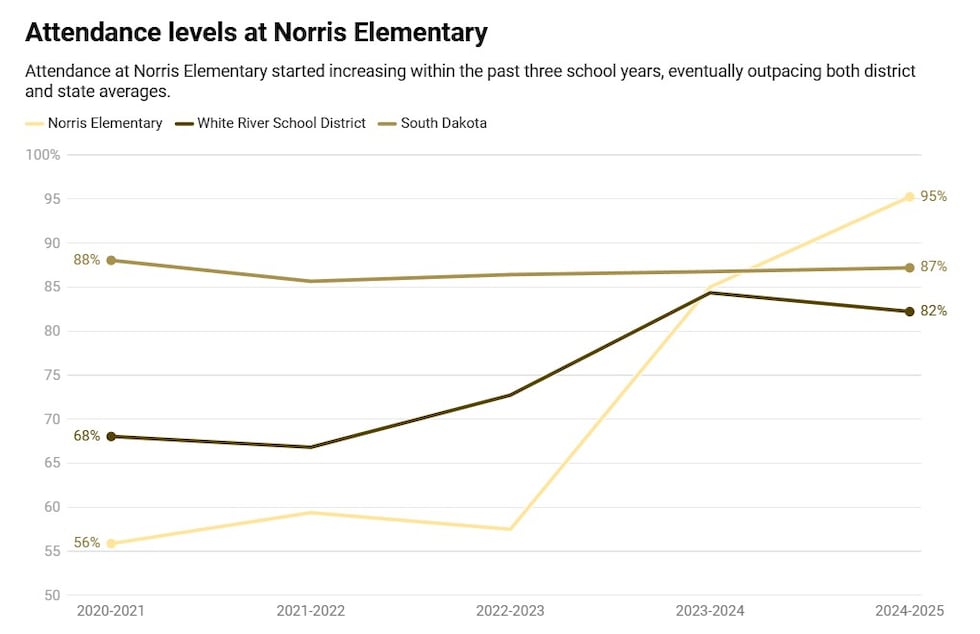

Three years ago, barely half of the school’s students were coming to class regularly. That struggle is common for schools serving Native American students in the state, according to data from the state Department of Education. Last school year, nearly half of Native American students were chronically absent, more than double the statewide rate.

But now, Norris’ attendance is above 90%. That’s higher than both the district and state averages. It’s been achieved by engaging one-on-one with students and families and implementing Lakota language and cultural programming.

The improvement is a source of pride for Brown and his staff.

“We can do it,” he said. “We can be successful, we can show people that we care about school and that we want to be the best that we can be.”

South Dakota Secretary of Education Joseph Graves has noticed the improvement. He said keeping students engaged through culturally relevant lessons and communication is an important part of replicating what’s happening at Norris.

“But it’s also that leadership, those people who are willing to make that happen, engage with kids,” Graves said. “You put those two together and it’s proven to be a very strong factor in the success.”

Graves said he wants to keep watching the school, to see if the trend continues and if it leads to increased proficiency and graduation rates.

The geographic isolation at Norris makes it difficult to hire and recruit teachers and staff. Two teachers are in dual-grade classrooms, the school’s head custodian and office administrator are also the school’s bus drivers, and Brown steps in at lunchtime to help serve food.

“We kind of have to make and manipulate our own resources just to get the kids what they need,” Brown said. “It’s been challenging, but then also, it’s been eye-opening to address the needs of the kids out here at Norris.”

Norris is one of many schools across the state trying to fill teaching positions. As of July, there were 144 open teaching positions, according to data from Associated School Boards of South Dakota.

A part of Brown’s morning routine is checking in with teachers during breakfast to ask which students they haven’t seen yet. If they aren’t there for roll call, Brown hits the road for a home visit.

He would’ve been doing that on a recent morning, he said, if he wasn’t talking to a reporter.

“I probably would’ve already went out this morning, and probably would have went and visited at least two houses this morning to parents and say, ‘Hey, how’s it going? What do you need? How can I help you?’” he said.

It’s not just about getting the kids to school. It’s about them wanting to come to school, Brown said.

In a small community, it takes everyone to keep students involved, said Wendy O’Brien, who teaches fourth and fifth grade at Norris.

“If you get the community members involved, and they come into the classroom and see what the kids are doing, I think they’re more supportive,” she said.

She wants students to form habits of good attendance. It’s especially important for students in her two-grade classroom.

“When they miss school, they miss learning,” O’Brien said. “Working with two grades, you don’t have time to reteach lessons.”

It’s also important to make the kids feel seen, Brown said. After taking over as principal in 2022, Brown, who works to preserve Lakota language, songs and philosophy, started finding ways to include Lakota culture in the school day.

Now, the morning announcements are followed by a group of students leading the school in Lakota songs. He also teaches Lakota studies to each grade once a week, and started the school’s first traditional Lakota drum group: the Black Pipe Singers.

“When children know their identity, they know who they are, where they come from, they will excel better academically and in basic life skills,” Brown said.

It’s one of the ways he can set students up for success before they get to high school, where more than one-third of Native American students in public schools don’t graduate, according to recent state data.

Brown calls the habits learned in elementary school the “bread and butter” of a student’s academic journey.

“It’s important to go to school every day, be on time, do the best that you can and work hard,” he said. “It promotes a more successful life for the children, and that’s what we try to establish here at Norris.”

Meghan O’Brien is the audio reporter for South Dakota Searchlight where she covers the state government and its impact on South Dakotans. She’s previously reported in Nebraska with a focus on health care and rural communities across the state.

South Dakota Searchlight is part of States Newsroom, the nation’s largest state-focused nonprofit news organization.

See a spelling or grammatical error in our story? Please click here to report it.

Do you have a photo or video of a breaking news story? Send it to us here with a brief description.

Copyright 2025 KOTA. All rights reserved.