Identification of lytic phages in bacterial assemblies

To identify complete lytic bacteriophage genome sequences within bacterial genome assemblies (BAPS), we developed a comprehensive bioinformatic workflow (Supplementary Fig. 1), starting with assembly data available from NCBI. We filtered and analysed 3.6 million bacterial assemblies, focusing on contigs between 5,000 bp (base pairs) and 1,000,000 bp as potential phage candidates. These contigs were analysed with Phager (version 0525), our feature-based machine learning tool developed in this study to predict phage contigs. Phager rapidly evaluates the likelihood that a contig represents a phage genome without relying on sequence similarity, thereby overcoming limitations to identifying highly divergent or underrepresented phages. The tool achieves this through the use of biological and compositional features and performs with markedly lower computational cost than large-scale similarity searches, allowing for fast, large-scale screening of assemblies. As a result, we extracted 3.5 million contigs of putative phage origin from the analysed bacterial assemblies.

These contigs were screened against reference databases to determine whether they originated from bacterial, plasmid or phage sequences. In total, we identified 119,510 lytic phages, 146,575 temperate phages and 602,285 plasmids. Phage sequences were further clustered based on average nucleotide identity (ANI) to distinguish lytic from temperate types.

The recent study by Dougherty et al.5 independently reported the presence of virulent (nontemperate) phage genomes within Escherichia assemblies. Dougherty et al. present detailed observations in E. coli and experimentally demonstrated persistence. Our large-scale screen shows that these events extend beyond E. coli, occurring broadly across bacterial taxa and indicating that active lytic phages are intrinsically linked to bacterial genomes.

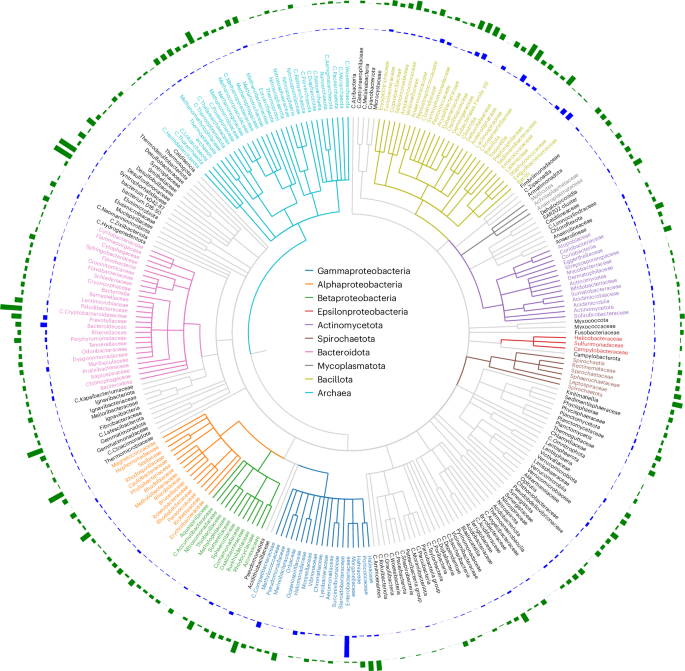

The distribution and abundance of BAPS contigs within all bacterial genome sequences is shown in Fig. 1. Mapping the bacterial host for each BAPS to a reference bacterial phylogenetic tree reveals the widespread presence of lytic phage genomes within bacterial genome assemblies of diverse origins. The metadata associated with these assemblies confirms that BAPS-containing bacteria were isolated from a wide range of sources, including human, animal, food, clinical and environmental samples spanning aquatic, terrestrial, wastewater and industrial settings, with metadata also indicating their collection from numerous geographically distinct locations worldwide.

The circular phylogenetic tree displays bacterial families, with each bacterial class colour coded according to the legend inside the circle. Only families with at least five observed BAPS are shown. The outer blue bars indicate the number of BAPS found per bacterial family. The outermost green bars represent the ratio of BAPS to the total number of genomes available for each family. C. stands for Candidatus.

Clearly, if BAPS are distributed evenly across bacterial taxa, the largest numbers will naturally be found within bacterial species that have been extensively sequenced, such as those targeted in clinical surveillance or outbreak investigations. To determine how sequencing bias relates to BAPS discovery, we examined the ratio of BAPS relative to the total number of genome assemblies available for each bacterial taxa.

The Gammaproteobacteria have the highest absolute number of BAPS, accounting for 33% of all BAPS contigs (39,755 out of 119,510). This largely reflects the overrepresentation of Enterobacteriaceae genomes in public datasets, particularly E. coli and Salmonella spp., which are frequently sequenced in clinical and surveillance studies. BAPS are also common within the phylum Bacillota, where they account for 25% of all BAPS contigs. Several clinically important Gram-positive families harbour BAPS contigs at appreciable levels, including Staphylococcaceae (3.7%), Streptococcaceae (2.9%), Enterococcaceae (0.7%) and Clostridiaceae (0.7%).

In addition to these well-studied pathogens, BAPS are also found in environmental taxa, even where sequencing effort is limited. For example, within the Alphaproteobacteria, BAPS are present in 13% of Roseobacteraceae, a family abundant in marine environments and 22% of Acetobacteraceae, which are common in plant- and insect-associated niches, indicating that the phenomenon spans diverse ecological contexts.

Overall, our analysis of bacterial classes and families (Fig. 2) highlights consistent patterns of BAPS distribution, with lytic phage genomes embedded within bacterial assemblies across diverse environments and hosts.

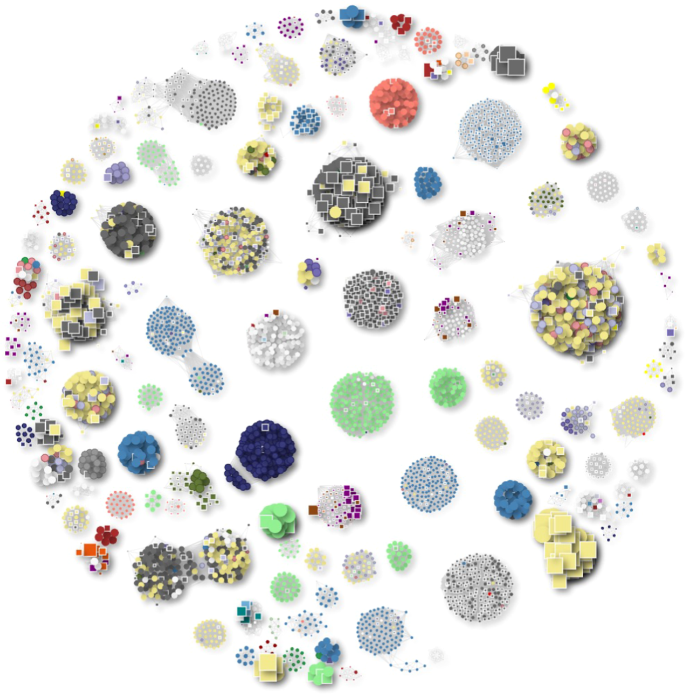

Each cluster shown consists of at least five members, including both phages from the NCBI database and BAPS phages. Phage genomes are represented as circles, while BAPS genomes are depicted as squares. The size of each shape is proportional to the genome size. Clusters are colour coded based on the host genus: Pseudomonas (light green), Klebsiella (blue), E. coli (khaki), Salmonella (dark grey) and Serratia (red).

Given the dominance of BAPS within the Enterobacteriaceae, we focused our analysis on BAPS associated with Salmonella spp. and E. coli where we identified six distinct lytic jumbo phage lineages. In several cases, the number of known members within a given lineage has now expanded dramatically. For example, the genus Seoulvirus has increased from 20 reference phage genomes in GenBank to over 300 complete genomes.

Similarly, the orphan jumbo phage genus Goslarvirus, originally represented only by the phage Goslar6,7, has been expanded from 1 to 237 genomes in our dataset.

Our approach has also led to the discovery of a new jumbo phage genus, for which we propose the name ‘Bapsvirus’. In total, we identified 247 BAPS genomes within this cluster, with the largest 54 genomes each ~220 kb in size. These phages are associated with Salmonella spp., E. coli and Shigella spp., illustrating that bacterial genome assemblies represent a valuable and untapped resource for phage discovery.

Expansion of existing Salmonella jumbo phage groups

Seoulvirus—major expansion of a therapeutic phage genus

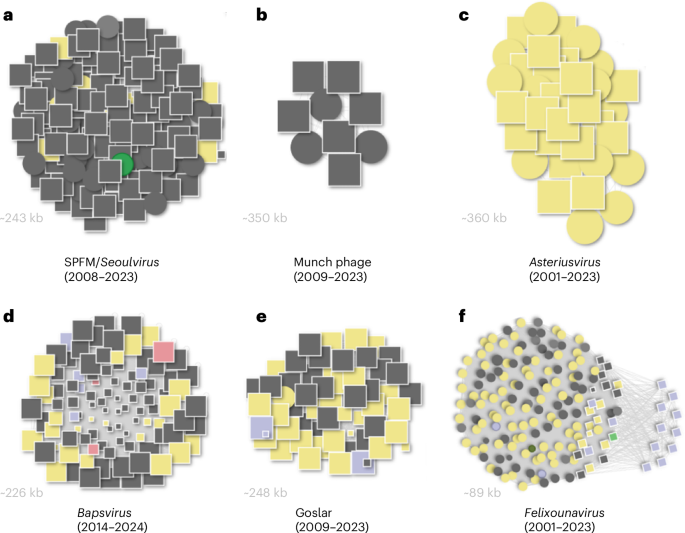

The largest BAPS cluster identified within Salmonella and E. coli genome assemblies belongs to the genus Seoulvirus, family Chimalliviridae. We identified >300 previously undescribed Seoulvirus genomes (239–242 kb), expanding the known diversity by more than an order of magnitude (Fig. 3a). These phages are well-characterized lytic viruses with documented therapeutic potential against Salmonella spp.8. The widespread detection of Seoulvirus BAPS across human, animal and environmental isolates underscores a stable and pervasive host–phage association in diverse environments.

a, SPFM/Seoulvirus lineage (2008–2023; ~243 kb). b, Munch phage lineage (2009–2023; ~350 kb). c, Asteriusvirus lineage (2001–2023; ~360 kb). d, Bapsvirus lineage (2014–2024; ~226 kb). e, Goslar lineage (2009–2023; ~248 kb). f, Felixounavirus lineage (2001–2023; ~89 kb). Each circle denotes a known phage genome from NCBI, and each square a BAPS-identified genome; node size is proportional to genome length. Phage and BAPS genomes are connected when sharing a Mash distance of ≤0.1. Colours indicate bacterial host genus: grey, Salmonella spp.; yellow, E. coli; green, Clostridium spp. (likely misannotation); pink, Shigella spp. The clusters highlight distinct jumbo phage lineages and show how BAPS discoveries expand previously known Salmonella-associated groups.

Bapsvirus—discovery of a new jumbo phage genus

Our approach also identified a distinct cluster of 247 BAPS genomes (~220–249 kb), representing a new jumbo phage genus, for which we propose the name Bapsvirus (Fig. 3d). These phages show limited sequence similarity (15–40% ANI) to Seoulvirus but retain conserved genome architecture and synteny. Most BAPS contigs were found in Salmonella genome assemblies, with additional sequences in E. coli and Shigella. Phylogenetic analysis supports the classification of Bapsvirus as a separate genus within the family Chimalliviridae, targeting bacterial cells of the Enterobacteriaceae. Further analysis of high-quality genomes within these two genera using taxMyPhage (version 0.3.6)9 expanded the number of species in Seoulvirus from 1 to 6 and identified 32 previously undescribed species in the genus Bapsvirus.

‘Munchvirus’—a widely distributed Salmonella phage genus

BAPS analysis uncovered several additional jumbo phages related to the rare 350 kb phage Munch, tripling its known relatives and spanning diverse Salmonella isolates (Fig. 3b). Together with known phages Munch, PHA46, SE-PL and 7t3, they form a single genus based on taxMyPhage analysis. We propose they are classified as a new genus ‘Munchvirus’, after the first isolate. Our BAPS analysis shows that phages within this group are globally distributed.

Asteriusvirus—expansion of an E. coli jumbo phage genus

We identified 189 BAPS related to Asteriusvirus, expanding this group of E. coli-infecting jumbo phages (350–380 kb, ~34% GC content) from a few genomes to a much larger dataset (Fig. 3c). Taxonomic classification increased the number of species from 2 to 14 and revealed a previously unknown related genus containing 4 species, confirmed by phylogenetic analysis. We propose the genus name ‘Lethbridgevirus’ after the submitting organization. Those were identified across E. coli genome assemblies from diverse geographical regions and environments, confirming that Asteriusvirus phages are globally distributed, with the freshly identified Lethbridgevirus capable of infecting both E. coli and Salmonella. This is consistent with the evidence presented by Dougherty et al. that virulent jumbo phages, especially Asterius-like lineages, are abundantly found in E. coli assemblies across regions and environments, indicating globally distributed, persistent phages beyond isolated genomes5.

Felixounavirus

We identified 114 BAPS contigs related to phages in the genus Felixounavirus, a well-studied group of phages that have been suggested to be useful for Salmonella biocontrol10.

Goslar phage—variable abundance in genome assemblies

To test whether phage contigs could be identified using a reference genome outside the Salmonella phage sequence space, we selected the orphan E. coli phage vB_EcoM_Goslar. BlastN searches confirmed that Goslar has no close relatives among known phages; however, using the BAPS pipeline, we identified 237 matching contigs. These contigs are a globally distributed group of putatively lytic phages that infect pathogenic Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae (Fig. 3e), recovered from diverse environments and hosts, including water, humans, cattle, pigs, chickens and bonobos, across diverse geographic regions. Goslarvirus sequences were associated with a wide range of E. coli serotypes and pathotypes and expanded into multiple Salmonella serovars and Shigella species. Taxonomic classification expanded the number of species from 1 to 38.

The widespread recovery of Goslarvirus contigs across such diverse hosts and environments highlights the broad ecological success of this previously unrecognized lytic phage lineage. To further characterize these phages and assess their potential impact on bacterial genome assemblies, we examined the relative abundance of Goslarvirus genomes within their respective sequencing datasets.

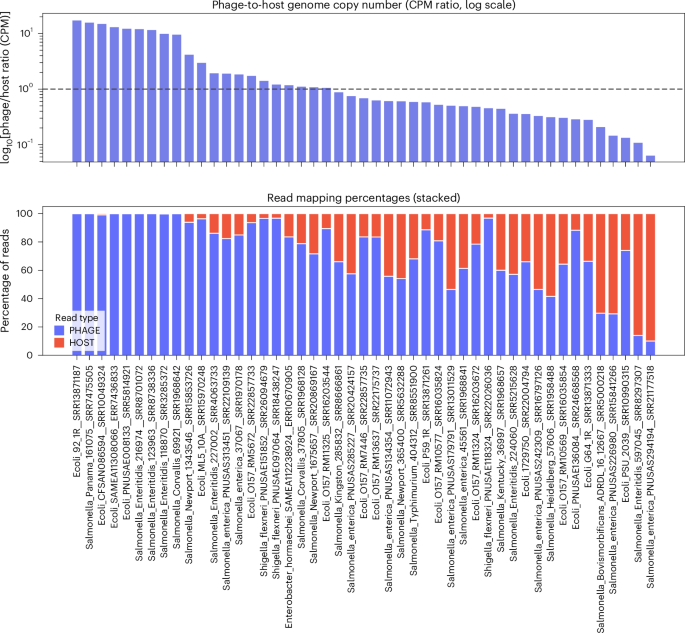

Read mapping of 55 representative assemblies revealed striking variation in the proportion of reads that map to phage versus host genomes (Fig. 4).

Phage–to–host ratios were calculated from counts per million (CPM) values, normalized for both contig length and library size. Top: phage-to-host ratios on a log10 scale. A dashed line at 1 represents the temperate baseline (~1 phage genome per host genome). Ratios below 1 suggest fewer phage genomes per host (carrier state or pseudolysogeny), whereas ratios above 1 indicate higher phage genome copy number than host, consistent with clarified lysates or active replication. Bottom: percentage of sequencing reads mapping to host (red) and phage (blue) contigs, shown as stacked bars. Together the panels illustrate striking differences in phage representation across bacterial assemblies, with some dominated by phage sequences and others showing balanced or host-dominated profiles. The labels on the x axis show the sample names from which the phage and host contigs were recovered.

In some cases, Goslarvirus reads dominated the dataset, consistent with high-titre phage presence at the time of DNA extraction, whereas in others, phage sequences were present at very low levels. For example, in Salmonella Newport 134356, 99.2% of reads mapped to a 237 kb Goslarvirus genome, while only 0.8% mapped to the bacterial chromosome. By contrast, other assemblies showed very low phage representation, such as Salmonella enterica PNUSA294194, where only 0.6% of reads mapped to a 239 kb Goslarvirus genome. Intermediate cases were also observed, such as Shigella flexneri PNUSAE118324, where reads were nearly evenly split between host (50.7%) and phage (49.3%).

This variation likely reflects differences in infection dynamics, contamination or DNA extraction protocols that favour phage particles. These findings show the need to consider phage content when interpreting bacterial genome data, particularly in clinical or surveillance settings where high phage abundance may influence assembly quality and downstream analyses.

Therapeutic and microbiome relevance of BAPS

It is interesting to speculate whether analysing BAPS can inform the selection and potential behaviour of phages that are used during therapy and to determine whether BAPS represent previously undiscovered sources of therapeutically relevant phages. To answer this, we looked to see whether known therapeutically relevant phages had BAPS homologues. The presence of therapeutically related phages in BAPS would support the idea that human and animal exposure to these phages is part of natural bacterial dynamics and thus support the idea that they are safe or at least ‘nothing new’. It may also have relevance to the presence of neutralizing antibodies for these particular phages within the human/animal body.

To evaluate how phages previously used in therapy relate to these relationships, we examined 66 therapeutic phages with publicly available genomes (Supplementary Table 3). These are all lytic phages that were previously used in human or animal therapy. Of these, 55 showed at least one BAPS match with moderate genetic similarity (roughly corresponding to ≥80% ANI), and 39 had highly similar counterparts (≥95% ANI).

Several BAPS equivalents were seen in 18 distinct clusters of therapeutically relevant phages (Fig. 5). A large E. coli phage cluster containing phage T4 (ref. 11) included phages used in clinical or animal studies by Bruttin and Brüssow12, Guo et al.13 and Pirnay et al.14.

Each node represents a phage genome: circles denote lytic phages from Genbank, and squares represent lytic phages discovered within BAPS bacterial assemblies. Nodes outlined in red indicate phages that have been used in published phage therapy studies12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. Edges connect genomes with a Mash distance of ≤0.1, indicating high sequence similarity. Colours represent host genera.

Similar patterns of BAPS similarity were observed for other therapeutically relevant phages. This included Shigella sonnei Mosigiviruses and Tequatroviruses15, Proteus mirabilis phages16, multiple Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage clusters, and OMKO1 and PA1Øand, two Klebsiella pneumoniae phages previously used in human therapeutic interventions14,17. A large cluster associated with Staphylococcus aureus comprised phages used in therapy studies18,19,20 and others, many of which had highly similar BAPS counterparts, indicating that therapeutically useful phages are naturally represented within the BAPS dataset.

Multiple BAPS contigs are found associated with human bacterial pathogens, including Acinetobacter baumannii, P. aeruginosa, P. mirabilis and K. pneumoniae. Phages used to target the opportunistic pathogen Bacteroides fragilis and the cystic fibrosis-associated Achromobacter xylosoxidans were also found as BAPS in a limited number of bacterial assemblies. BAPS with high similarity to phages previously used against Gram-positive opportunists such as S. aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis were also observed. To assess this systematically, we screened 66 lytic phages with published therapeutic use against our full BAPS dataset. Of these, 55 (83%) matched at least 1 BAPS contig with a Mash distance of ≤0.2, and 39 (59%) had highly similar counterparts with a Mash distance of ≤0.05. A small number of phages, including Listeria phage P100 (a component of the commercial product Listex P1007), had no close BAPS representatives.

Although the most highly populated BAPS cluster mapped to P. aeruginosa phage PA1Ø (n = 3,146), a lytic variant of the temperate phage D3112, no further analysis was conducted on this phage due to its temperate origin, which makes its presence in bacterial assemblies expected.

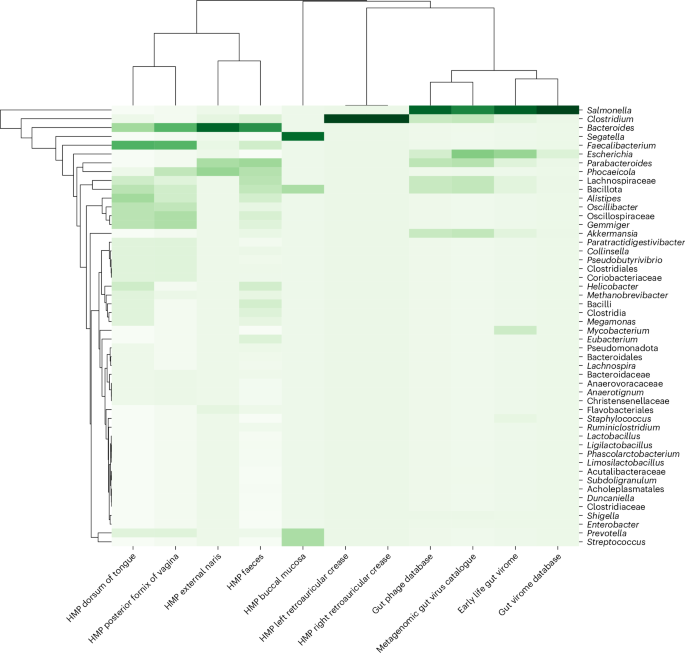

We also investigated whether BAPS phages were detectable in the human microbiome (Fig. 6). Across four major gut virome datasets (Metagenomic Gut Virus (MGV), Gut Phage Database (GPD), Early Life Gut Virome (ELGV) and Gut Virome Database v1 (GVDv1)) and one whole metagenome dataset (Human Microbiome Project (HMP)), nearly 2,000 BAPS contigs were identified, with high ANI > 96% across most hits. Although the number of matched metagenomic contigs varied between databases, several BAPS phages appeared consistently across multiple catalogues, supporting their ecological relevance in human microbiomes. Many of these matched contigs were in the 230–240 kb size range, consistent with jumbo lytic phages.

Clustered heat map showing the distribution of BAPS phage contigs detected across various human-associated metagenomic datasets, including the HMP, MGV, GPD, ELGV), and GVDv1. Columns represent different datasets, while rows indicate the top 50 bacterial genera associated with BAPS phages based on taxonomic annotation of matched contigs.

Together, these findings suggest that BAPS are present in clinical and environmental bacterial isolates and may also persist in human-associated microbial communities. While not central to the main conclusions of this study, their presence in metagenomic datasets suggests broader ecological relevance and supports future efforts to explore their in situ dynamics.

While most bacterial assemblies containing BAPS contigs were consistent with the bacterial species recorded in the corresponding genome metadata, we identified a small subset where the taxonomic assignment of the bacterial assembly did not match the true bacterial source based on sequence validation. These misclassifications can lead to seemingly implausible phage–host associations. For instance, 11 complete lytic phage genomes within Legionella assemblies is an exciting prospect given the current lack of known lytic phages for this pathogen. However, our taxonomic validation pipeline (Methods) revealed inconsistencies in these cases, suggesting that the actual bacterial source of the assemblies may not have been Legionella. A similar example appears in Fig. 5, where one BAPS genome originally annotated as Clostridium perfringens clusters tightly with known Staphylococcus phages. Detailed inspection confirmed that the underlying contigs were in fact of Staphylococcus origin.