Salmon are one of California’s most iconic species. The powerful fish is famous for its long migration from the rivers to the ocean, and their final, fatal return to their spawning grounds.

Once abundant across the state, the salmon also has deep cultural ties for local tribes. But decades of overfishing, dam construction and the ongoing impacts of climate change have left salmon populations a shadow of what they were at their peak.

Significant efforts have been made to help salmon bounce back in recent years. One notable example was the removal of several decommissioned hydroelectric dams along the Klamath River near the California-Oregon border last year, the largest dam removal project in U.S. history.

Last month, Oregon wildlife officials said Chinook salmon have been spotted returning to historic spawning habitats in the Klamath that had been inaccessible for more than a century.

As these restoration efforts are ongoing, some salmon experts are also wondering whether it is time for California to rethink its cultural connection to these fish.

Carson Jeffres is a Senior Researcher at the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences. He has more than two decades of experience studying and working with salmon, including with tribes like the Winnemem Wintu in the McCloud River watershed.

Jeffres spoke with Insight Host Vicki Gonzalez about what it would mean for California to rebuild its “salmon society,” and reintroduce this migratory fish into art, storytelling and the cultural mindset.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Interview highlights

What makes California’s salmon unique compared to other parts of the country?

The abundance and the size of the California population used to be unimaginable. That’s because we don’t have these other species of salmon, we just have the Chinook… four species of Chinook salmon that will come at different times of the year.

An illustration by Blane Bellerud showing how the Winnemem Wintu and other tribes lit fires along the river, believing they would help guide the fish upstream.Courtesy of Carson Jeffres

An illustration by Blane Bellerud showing how the Winnemem Wintu and other tribes lit fires along the river, believing they would help guide the fish upstream.Courtesy of Carson Jeffres

But we’ve really lost it. When we did have millions of fish, that provided the abundance people relied on. And, the salmon feed the rivers when they come back and they lay their eggs. When you have millions of fish coming back and die, they’re providing the nutrients in the river system for their young. There’s a saying: be a good ancestor, not a good descendant. They are providing for future generations when they come back and pass away.

What would you like people to better understand about salmon’s deep cultural ties?

Lots of the origin stories of the indigenous communities come from salmon, or are centered around salmon. And even in California, as early as the late 1800s-early 1900s, we had such an abundance of salmon. There were canneries all throughout California… up until the early 1900s there was even a cannery in West Sacramento, which seems inconceivable now. We were able to [have] canneries even after 50 years of degradation from gold mining, levee building, dam building.

California’s salmon are resilient, but they have experienced significant population declines in the past decades. What do you attribute these drops to?

I think the salmon is truly a case of death by a thousand cuts. We’ve had habitat degradation. We’ve had the dams, the levees, water changes, as well as changing climate. We’ve seen things in the ocean, where they live for multiple years, change. [There are] warmer droughts here where we see migrations are really struggling. It gets too warm, the water is low.

We have a hard time keeping fish in places where they never were supposed to be historically. When we put the dams in, they lost access to all of the high-elevation habitats that were cooler during the summer [and] provided opportunities for migration. And so, it’s been all of these things together that have led to the decline that we’ve seen really over the last couple decades.

When do you think California lost its “salmon society,” and why?

I think it was really at the turn of the 1900s, that’s when we really lost the abundance. With the loss of abundance we developed a whole bunch of the habitats around the system for other uses, and it became a secondary component of who we are. We went to more of an agriculture, urban environment where salmon were no longer part of our local meals, they weren’t part of our local traditions.

The Oroville Optimist Club barbeques salmon donated by Enterprise Rancheria during the 25th anniversary of the Oroville Salmon Festival held in Oroville, California. Photo taken September 28, 2019.Florence Low / California Department of Water Resources

The Oroville Optimist Club barbeques salmon donated by Enterprise Rancheria during the 25th anniversary of the Oroville Salmon Festival held in Oroville, California. Photo taken September 28, 2019.Florence Low / California Department of Water Resources

As we lose that localism, we lose that idea [of] having them be an integral part of our society. We’re not getting rid of our agriculture… or our cities because that’s where we live. But, can we have this idea where the average person knows the importance of these fish in our local environment? In downtown Sacramento even right now, there are tens if not hundreds of thousands of salmon swimming by.

You wrote a blog post about rebuilding our salmon society. What does that mean to you?

I’ve been working on trying to rebuild salmon populations for over 20 years now, and I look at what we’ve done and it’s been slow. We’ve seen nothing but populations decline.

Last year we were working [on] a project with high school kids and one of the kids asked me, why do I do this? And I had to think about it for a second. And then I realized, “well, these are your fish.” These are the next generation’s fish, and these students are ultimately going to be the ones making decisions.

If we want to have salmon back in abundance again it has to be societal change. We can’t start our 100-year plan in 99 years and expect it to work.

Are there other states that are a “gold standard” for keeping their salmon society intact?

When you look in the Northwest… if you get off an airplane in Seattle or Portland or Vancouver, one of the things in the public art is salmon. In Sacramento when you get off [at] the airport there’s the river on the floor. There’s agriculture, there’s birds, but there isn’t a salmon. My hope would be that as this evolves, is that salmon once again become part of our public art collective as well, it’s a symbol of who we are. I think that having salmon in that space is really important, it highlights what our value set is.

I think that to be a salmon society, you don’t have to love to eat salmon. You don’t have to love to catch salmon. But you have to love what they mean to us as a people.

Why is now the right time to start reestablishing these cultural ways of thinking about salmon?

Over the last decade we’ve really seen our populations of salmon crash. At the same time, we’ve had to close our commercial salmon fishery which has had a huge impact for the local communities along the coast and in the Central Valley. We’ve also had three wet years in a row, which is actually really anomalous. Those three wet years and no fishing have resulted in a pretty quick rebuilding of the stocks, we’re seeing great numbers come back this year.

You want to make hay while the sun is shining, and we got lucky… following several really significant droughts that were really hard on the populations. It’s a lot easier to support something when you can go out and see it, and right now, those fish are coming back in really good numbers.

How would you like to spark interest and storytelling about salmon among the younger generations?

When we work with high school and elementary kids, it’s so easy to talk about salmon. They still have the excitement. And when we talk to those kids one of the things that they always say is, “this is so cool. I go home, I tell my siblings about this, I tell my parents about it.” Over time, it’s that oral tradition. Those kids, they become the storytellers. And as they develop their stories around the salmon, they build up that salmon society. That’s one of the things that gives me hope.

When given that opportunity, it’s a story that’s really easy to tell. These fish being born as a small egg in the river, all the way out to the ocean and coming back…. it’s really a romantic story, and it’s a story of perseverance to get there.

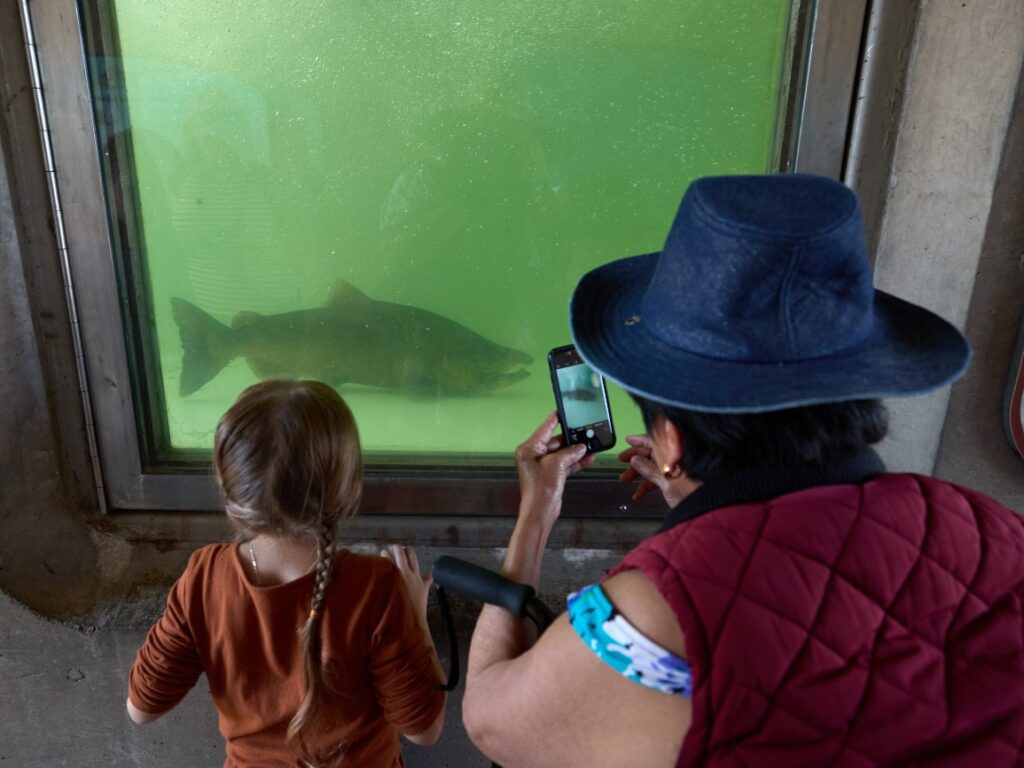

What are some local opportunities for people who want to see salmon being reintroduced into waterways?

Right now if you want to just go out on an unstructured space, you could go to Sailor Bar on the American River. There are actually salmon spawning out in the riffles there. Please don’t catch a salmon. They’re trying to do their thing. You’ll see the bodies that are out there as well that are ultimately going to the next generation.

There’s the Stanislaus River Salmon Festival on Nov. 8. Up in Oroville there’s tons of salmon spawning, if you walk around Bedrock Park you will see salmon… or the local creeks around Chico, the Yuba River, the Mokelumne has a lot of fish. I think any place you can get to, one of these salmon-bearing rivers below the major dams, you can see them and I promise you won’t be bored by what you see.

You can listen to more of Jeffres’ conversation here.

CapRadio provides a trusted source of news because of you. As a nonprofit organization, donations from people like you sustain the journalism that allows us to discover stories that are important to our audience. If you believe in what we do and support our mission, please donate today.