We know it’s a pain to ask for money—but here are the facts.

Since January, The Wild Hunt’s readership has soared past 400,000 views a month. That’s humbling—but higher reach also means higher costs. Hosting, technology, and reporting all add up.

Our editors are unpaid, and some of our staff volunteer their time. But we believe everyone deserves to be paid for their work.

We tried advertising once, and readers were flooded with Christian ads. That’s not who we are.

We’ll never hide our stories behind a paywall—our community deserves access, no matter their ability to pay. To keep Pagan news free, independent, and authentic, we rely on you.

A few hundred supporters pledging $5 a month—or more if you can—would keep The Wild Hunt secure for the year. If you’ve been thinking about supporting us, now is the time.

👉 This is how you can help:

Tax-Deductible Donation

PayPal

Patreon

As always, our deepest gratitude to everyone who has brought us this far.

Today’s review comes to us from Noelle K. Bowles. She teaches literature and writing courses at Kent State University at Trumbull, specializing in nineteenth-century British literature, the fantastic, creative writing, women’s literature, and the basic writing courses everyone loves to hate. When not preparing class materials or grading papers, she spends her time kissing her Frenchie, complaining about cat hair, cooking Indian cuisine, and shaping clay into ceramic monsters… oh, and reviewing television and film.

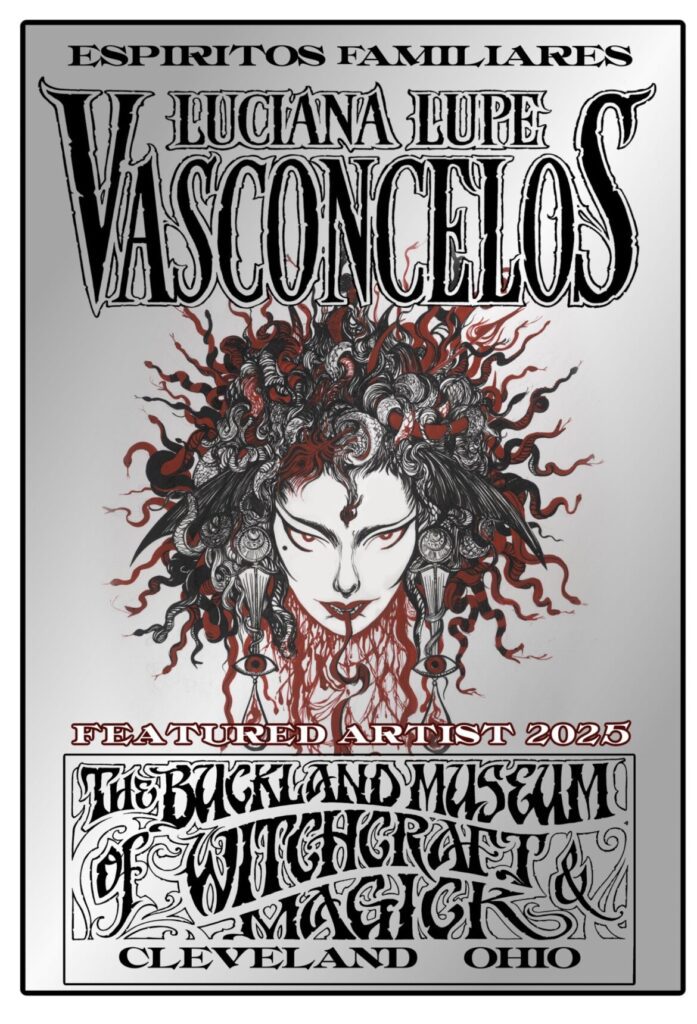

CLEVELAND – Luciana Lupe Vasconcelos (Brazil) is a self-taught artist whose works embrace the symbolic, occult, and mythological without hesitation or apology. Her heavy use of red and black makes an immediate graphic impact reminiscent of Aubrey Beardsley, and the images are hauntingly beautiful.

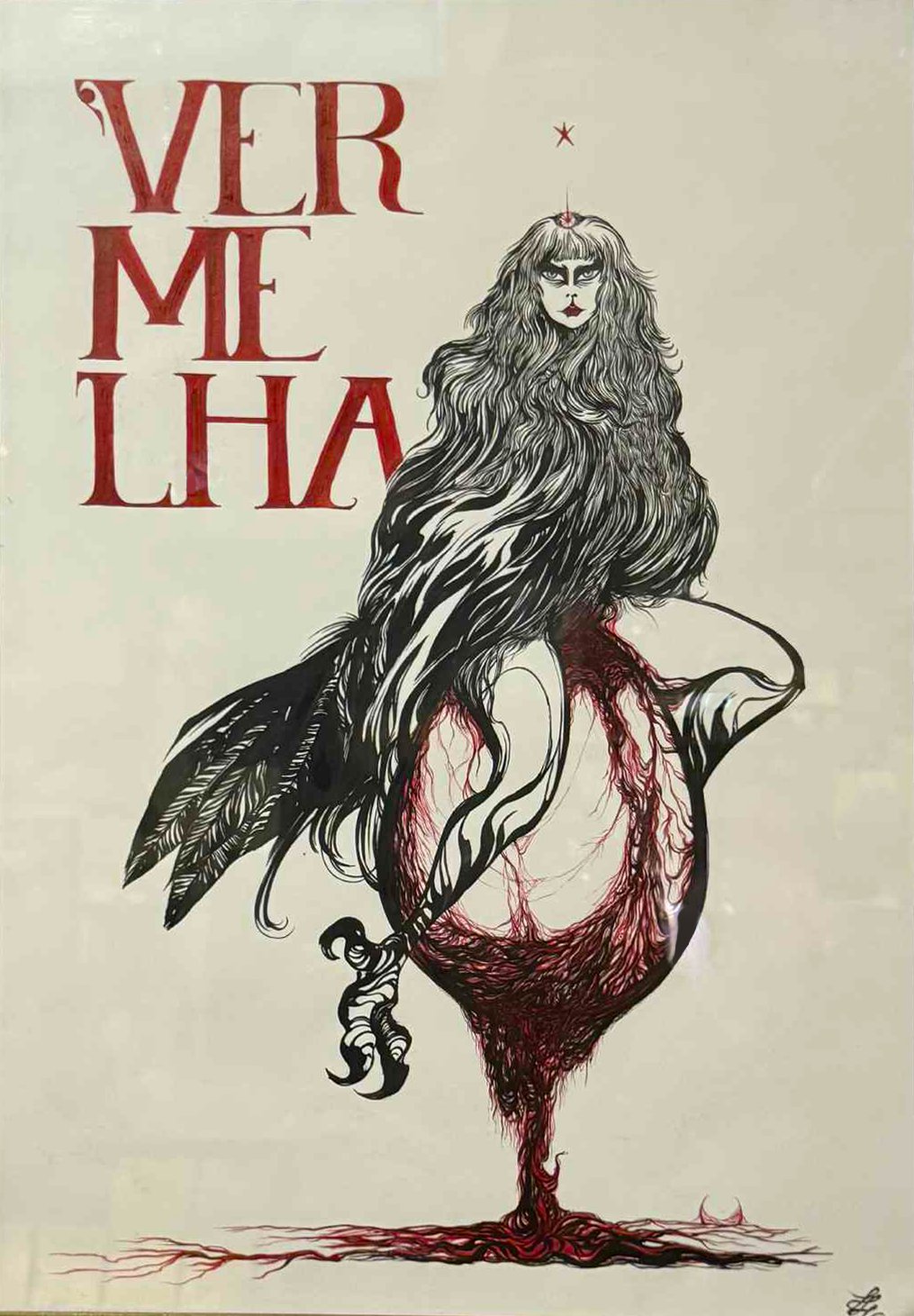

In this exhibition, Vasconcelos’ work is indeed “familiar spirits” for many images connect to mythological beings viewers will recognize, like the harpy who sits atop a blood-soaked egg in “Vermelha” (red in Portuguese). But Vasconselos’s creations are also “familiar” in the occult sense of the word.

The images radiate dark feminine energy of a talismanic and protective nature. “Harpy,” for example, does not have a positive connotation in contemporary culture. But the harpy of “Vermelha” perches as the guardian of potential life rather than punishing anyone or snatching people and objects from the mortal realm. The blood supporting and running down the egg works symbolically as the harpy’s sacrifice, as both menses and oviparity (reproduction via egg). Rather than turning away from female biology and symbols, Vasconcelos’s work revels in feminine creative and destructive potential.

Far from the “vampiric, child-eating boogeyman” of patriarchal lore, Vasconcelos’ Lamia lounges on her elbows with a secretive smile of satisfaction playing on her face. Her crown is evocative of Hathor (the Egyptian goddess of motherhood, music, love, and fertility), and this effectively undercuts the child-devouring monster of the original Greek myth. As with her other creatures, Vasconcelos transforms and reinvents Lamia in this powerful syncretic imagination. Although Lamia cradles a skull, its lines blend with her hair in a way that suggests death is simply a part of her, not the whole.

The image titled “Imbus” presents viewers with a host of symbols: a banner in a medieval style of a seven-spiked star, rather like HBO’s Game of Thrones interpretation of the central faith of Westeros. The half crescent and full moon in the woman’s peacock-fanned hair evokes pagan as well as Muslim traditions, while the glorious red wrapping that clothes her gestures toward Middle Eastern patterns and style. The rose represents beauty and femininity as well as danger, while the sword symbolizes strength and the ability to defend. Here, the sword has skewered an indefinable something that borders on the grotesque, so Imbus’s competence as a protector cannot be denied. In this, as in the other works, the artist empowers her creatures to tell and control their own narratives – stories that supersede their traditional representations as reviled female monsters.

The Buckland Museum of Witchcraft and Magick is a wonderful venue for these works and provides a welcoming space in these times when many (if not most) of us are feeling especially beleaguered. The number of works displayed is relatively small due to space limitations, but it is well worth viewing.

“Espiritos Familiares” will run from early October through December 2025. Please visit the Buckland Museum of Witchcraft and Magick website for more information and to order tickets in advance.

Image by Luciana Lupe Vasconscelos [Courtesy

Luciana Lupe Vasconcelos, an occult artist who resides in Teresópolis, Brazil. In 2021, Vasconcelos paired with the late Darcillio Lima at the Buckland Museum for an exhibit called “Magia Protetora”. This exhibit was masterfully curated by the Stephen Romano Gallery, NYC. Vasconcelos now sets off on her own with her beautifully haunting “Espiritos Familiares”. Known for her unique creative process, Luciana enters a trance state to channel spiritual energies, resulting in mesmerizing and otherworldly artworks.

This exhibit is co-curated by Luciana Lupe Vasconcelos and Toni Rotonda, for the exhibit at The Buckland Museum of Witchcraft and Magick. A special “Thank you” to the ancestors, our visitors, and to Steven Romano for the introduction to her work.

More of Vasconcelos’ work can be viewed on her Instagram.