What is it in Alaska today?

With the Great White Father and his co-conspirators in the faraway capital of these UnUnited States accused of trying to destroy the Alaska way of life, isn’t it time someone ask what exactly that is in the last quarter of the 21st century?

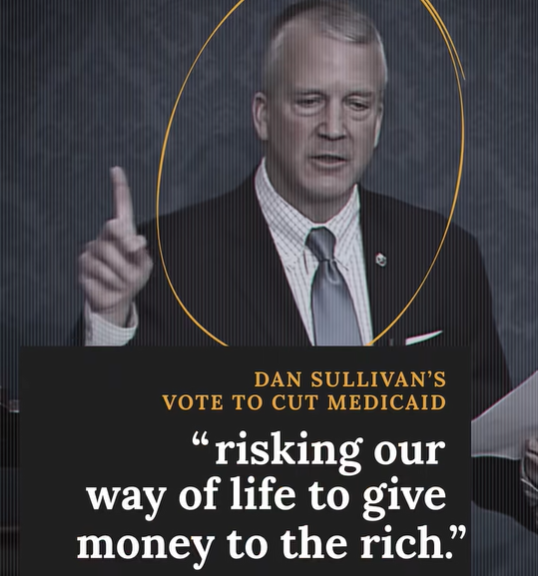

“Majority Forward” has swarmed YouTube with commercials claiming government-funded “health care” defines the Alaska way of life and that “Alaska cannot survive” cuts to Medicaid.

One really has to wonder if government-funded television and radio remain a “critical service” for emergency alerts in villages where almost everyone now seems to have a cellular phone and can be directly notified by the government rather than the government telling APM and hoping people are watching the TV or listening to the radio.

As for essential local connections, does APM truly believe it provides a better service than the social media now wiring villages together? (Editor’s note: The author is a big fan of the programming provided by the Public Broadcasting System (PBS), but a distinction needs to be drawn between TV programming and “critical services.”)

All of this sudden concern about the Alaska way of life has, of course, arisen because former President Donald Trump failed miserably to “drain the swamp,” as he promised on his way to winning the 2016 presidential election, only to lose the 2020 election, which helped to keep the swamp filled.

Then came Trump’s comeback win in November, and a whole new approach to the swamp.

Since resuming office this year, he and his Republican supporters have been hard at work doing all they can to reduce the flow of money that keeps the bureaucracy afloat there.

Inside-Outside influence

Washington, D.C. -based Majority Forward, which the Capital Research Center’s “Influence Watch” describes as a $20 million “Democratic Party-aligned advocacy group that campaigns against Republicans and conservative causes,” now claims planned budget cuts to Medicaid, an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services, could leave one out of three Alaskans without health-care coverage, and thus threaten the aforementioned way of life.

These claims would make it appear the Alaska economy is in worse shape than anyone thought, given that Medicaid was set up to aid people who are poor and unable to find decent jobs.

The minimum wage in Alaska is now set at $13 per hour, which puts minimum wage workers just above that bar if they work full-time, year-round.

Someone doing so would today make just a hair over $27,000 per year, which would suggest to anyone of even minimal intelligence that it would be good to skip work and go without pay for at least a week every year.

That would take $520 out of your pocket, but allow you to qualify for free, government health care (Medicaid) which is a way better deal than anyone is going to find with any “Affordable Care Act” (ACA) health insurance plan.

Medicaid also offers special help for minors and old folks. If the income of your family of four is less than about $83,600 per month, your kids may qualify for Medicaid, and if you are pregnant or gave birth within the last 12 months and you are in a family of four with an income under about $92,500 per year, you also may qualify.

How many Alaskans are taking advantage of these various components of Medicaid shifts by the month. But Medicaid.gov and KFF, an independent and reliable health policy organization formerly known as the Kaiser Family Foundation, in March put the number of Alaskans enrolled in the state’s $2.6 billion Medicaid program near 32 percent of the population.

Thirty-two percent is almost one out of three Alaskans, but how many of them – if any – might lose coverage due to Trump’s self-aggrandizing “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” is hard to say. Most of the Medicaid changes in the act are aimed at forcing childless, able-bodied adults ages 19 to 64 to do something or lose their free health care.

Some Alaskans have, however, been exempted from that so-called “community engagement requirement.” Among them, according to the Alaska Department of Health, are “Alaska Native and American Indian individuals, people who are pregnant or medically frail, individuals with complex health conditions, and caregivers of young children or people with disabilities.

“These exemptions,” the state adds, “may significantly reduce the number of people in Alaska affected by these new rules compared to other states,” some of which had previously required their residents meet work requirements to qualify for Medicaid.

The way of life

There are at this point no good numbers on how many people enrolled in Alaska Medicaid qualify for the state’s community-engagement exception, but the provision would appear to cover most of the 53 percent of state Medicaid recipients reported to be living in rural Alaska.

Rural Alaska, which up until about 100 years ago was almost all of Alaska, was for thousands of years home to the toughest and most adaptable humans in North America. Nobody survived sub-zero winters in homemade structures heated with mammal oil or wood obtained without chainsaws without being tough.

But a lot has changed in 100 years. The Alaska way of life shifted from a subsistence/survival lifestyle to a modern, capitalist lifestyle dependent on jobs and money. And jobs are hard to come by in rural in Alaska.

The number of people on Medicaid there underlines the crisis of unemployment or non-employment – people who just give up looking for work – in the state’s rural regions. Using U.S. Census numbers to define rural, there are about 273,000 rural Alaskans.

The statewide Medicaid numbers would thus indicate 46 percent of the rural population is on Medicaid. But the actual percentage is likely higher given that most of the people with jobs in rural Alaska work for government or tribal entities, which provide employee health insurance.

It would appear likely that over half of those living in rural Alaska, possibly well over half, are on Medicaid. The good news for the state is that a majority of these Medicaid recipients are Alaska Natives who qualify for the federally funded health care provided by the Indian Health Service (IHS).

They are usually on Medicaid as a supplement because it will pay for flights to the Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage or other urban hospitals. The IHS will not cover costs for airfare.

IHS medical care does, however, help hold down Medicaid spending in the 49th state. As a result, the per capita spending for Alaska Medicaid recipients comes out to only a little over $11,000 per year, which is about $400 above the national average for what it now costs to cover the medical expenses of more than 83 million U.S. residents on Medicaid.

And this Alaska cost comes despite some huge differences in medical costs between Alaska and the Lower 48.

West Virginia is below the national average for home care at about $37,125, but above the national average of $53,3400 for institutional costs, according to KFF. These two expensive programs are a large reason why, as KFF notes, “people ages 65-plus and people with

disabilities are 23 percent of Medicaid enrollees but account for 51 percent of spending.

As of May 1, about 1 million people were unemployed and looking for work in California, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. But Cal Matters, a news organization, notes the BLS number paints a rosier picture of the actual situation because it counts as working anyone who has held any job for as little as one hour per week.

Cal Matters argues that what is called the BLS U-6 number – defined as “total unemployed, plus all persons marginally attached to the labor force, plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as a percent of the civilian labor force plus all persons marginally attached to the labor force” – provides a more accurate portrait of those unable to find jobs.

By April of this year, the BLS was reporting the U-6 rate for California was up to 10 percent, still the highest in the nation. Alaska was at 8.4 percent on the U-6 rate, but the 49th state is uniquely under-reported in that it is home to a disproportionate number of people of working age who aren’t even “marginally attached” to the workforce.

The waiver for adults living in these villages was later amended to require work, but welfare program administrations were allowed to broadly define “work” in recognition of the lack of jobs. The Alaska Association of Village Presidents (AVCP), which administers the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) in Southwest Alaska, for instance, now cites these as “some examples of work activities:”

- Applying for employment (this activity is limited to a maximum of three hours per week)

- Subsistence activities

- Community service

- Studying to pass the GED exam

Subsistence is the Alaska term for hunting, fishing and or other wild food gathering.

Though Majority Forward pointedly spun its Medicaid messaging for Alaska to make it sound as if Sen Dan Sullivan, R-Alaska, and the 49th state were uncaring when it comes to offering help to those in need, a SmileHub examination of “States Most Supportive of People in Poverty” published this week put Alaska just outside the top 20 at number 21.

This came despite the state’s high cost of living. Only Massachusetts, California and Hawaii were reported to have higher costs of living than Alaska. The first two because of the astronomical costs of housing, and Hawaii due to the costs of transporting goods to islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Alaska ranked in the top 10 states for the income and benefits provided those in poverty, but scored in the lower 20 percent of states in the availability of transportation and education. The former is something to be expected in a state with almost no rural highway system, and the latter is a reflection of the education provided by small rural schools highly dependent on who can be recruited to teach in remote and isolated areas where some parents aren’t all that interested in their children getting a 21st-century education.

A bad score in housing, healthcare and food likely stemmed from cost factors for groceries in rural Alaska with no consideration given to the semi-subsistence lifestyle that allows many to supplement their food supply with wild fish and game, sometimes while claiming a welfare-protecting work credit to do so.

Medicaid cuts could conceivably hurt some in poverty in Alaska. But an end to the Alaska way of life because of Medicaid seems a reach even if one defines life on government assistance as the new Alaska way of life.

Jobs

Two-thirds of the population would appear to include work as part of the Alaska way of life, and the bigger problem than Medicaid in rural Alaska is the lack of work.

Because of this, rural Alaskans have been steadily migrating to Alaska cities for years now. Those who stay in rural areas increasingly live on welfare of one or various sorts and dividends from Alaska’s Native corporations.

“Due to migration from rural to urban areas, the proportion of the Alaska Native (alone) population living in boroughs that were 10 percent or less Alaska Native alone grew to 41

percent in 2019, up from 38 percent in 2010, according to the Alaska Department of Labor.

The only thing that has kept rural Alaska from depopulating even further and faster is a birth rate one and a half to two times higher than the state average.

The state Department of Labor reports the highest Alaska birth rates were in some of the state’s poorest areas. The Kusilvak Census Area had the highest average annual rate from 2010 to 2019 with 3.0 births per 100 women, followed by the Bethel Census Area (2.4), Northwest Arctic Borough (2.4), and Nome Census Area (2.3), according to the agency.

Because of the lack of employment, many of working age have left the region. According to the Census Reporter, 45 percent of the population is 19 or younger, and 11 percent is 60 or older.

“Federal grants for such programs grew sharply in recent years….Three-quarters of the new jobs created in remote areas in the 1990s were in service industries. Remote areas gained some basic industry jobs (in mining and petroleum) in the 1990s, but many of these jobs are held by non-residents.”

The state and federal governments, either directly or indirectly, continue to be the biggest job providers of these jobs. “In many rural areas, nonprofits account for up to half of non‐government employment,” the Alaska Humanities Forum reported in June.

The nonprofits are, however, primarily funded by government grants. The Foraker Group, which monitors nonprofits and classifies them as second only to the oil and gas industry as an economic force in the 49th state, describes these entities as “leverag(ing) public funds for maximum return.”

The Group describes them as government partners that gained access to $2.5 trillion during the Covid-19 pandemic and $7.6 billion from the Biden administration’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

This money is why nonprofits are today a big part of the rural Alaska economy, and they have helped health care become an economic engine there. Decades ago, ISER analysts saw this coming with rural areas getting better health care while suffering ever-worst health.

“Improving village living conditions has been a long process that isn’t finished yet,” they reported, “but the federal and state governments have made major progress.

“Today, the health problems among Alaska Natives are, like those of other Americans, related more to behavior than to living conditions. Genetics, living conditions, and medical

care together account for about half of life expectancy. The other half – as much as all the other factors combined – is behavior.

“And as all of us know, changing behavior isn’t easy. Eating too much of the wrong kinds of foods, smoking, and not getting enough exercise have helped spread diabetes, heart disease, and other problems among Americans for decades. Such health problems are now also widespread among Alaska Natives.”

Both in Alaska and nationally, Medicaid helps pay to treat the associated medical problems that arise for low-income Americans, but little to nothing is being done by any entity to change the behaviors leading to many of these health problems.

A better rural economy wouldn’t necessarily do much to solve the behavioral issues leading to ill health, but it would surely help to lower the Medicaid burden imposed on working Americans paying taxes to cover the costs of Medicaid.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics is now reporting South Dakota has the lowest unemployment rate in the nation. It has only 14 percent of its population on Medicaid, according to KFF.

North Dakota has the nation’s second-lowest unemployment rate, according to the BLS. It has 13 percent of its population on Medicaid, according to KFF.

Vermont unemployment comes in third lowest, but the Medicaid rate there is 26 percent, according to KFF. This could well be because Vermont shares a problem with Alaska – 58 percent of its residents on Medicaid live in rural areas with few jobs.

Sadly, since Vermont didn’t get the community engagement exception that Alaska got, meaning it could be the state with its “way of life” most threatened by the Trump administration.