Nasa

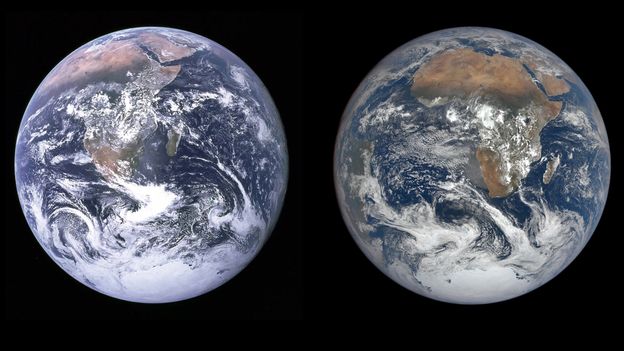

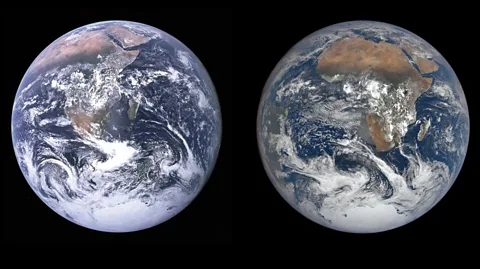

NasaThe “Blue Marble” was the first photograph of the whole Earth and the only one ever taken by a human. Fifty years on, new images of the planet reveal visible changes to the Earth’s surface.

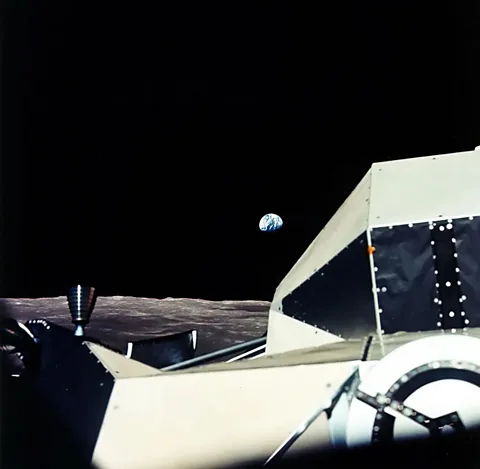

“I’ll tell you,” said astronaut Harrison Schmitt as the Apollo 17 hurtled towards the Moon, “if there ever was a fragile-appearing piece of blue in space, it’s the Earth right now”.

It was Thursday 7 December 1972, that humanity got its first look at our planet as a whole. In that moment, the photograph “The Blue Marble” was taken – one which changed the way we saw our world.

“I can see the lights of southern California, Bob,” said Schmitt to ground control about one and a half hours into the flight. “Man’s field of stars on the Earth is competing with the heavens.”

The crew of the Apollo 17 – commander Eugene Cernan, command module pilot Ronald Evans and lunar module pilot Harrison “Jack” Schmitt – were watching their home recede into the distance as they journeyed into space for the last manned mission to the Moon.

Looking back towards the Earth, Cernan commented: “the clouds seem to be very artistic, very picturesque. Some in clockwise rotating fashion… but appear to be… very thin where you can… see through those clouds to the blue water below.”

It is an enduring image of the beauty but also the vulnerability of our planet – adrift as it is in the vastness of the Universe, which hosts no other signs of life that we have been able to detect to date. But ours is also a planet of great change. The tectonic movements that shift the landmasses move too slow for our eyes to notice. Yet another force – humanity itself – has been reshaping our planet at a pace that we can see. Urbanisation, deforestation, pollution and greenhouse gas emissions are altering the way the Earth looks. So how, over the 50 years since that iconic image was taken, has the Blue Marble changed?

Nasa

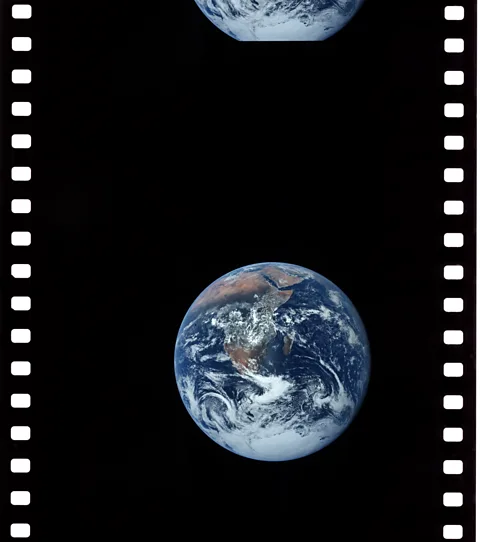

NasaThose first images of the Blue Marble were taken by the crew, who passed the onboard camera – a hand-held analogue Hasselblad 500 EL loaded with 70mm Kodak film – between them, captivated by the sight of the Earth from space.

“All the images captured with Hasselblads are spectacularly clear and bright,” says Jennifer Levasseur, curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC.

The camera was specially modified for use in space, she adds. Glues, lubricants, moving parts and batteries could all cause problems or fail when exposed to the extremes of hot and cold in space. It was also given a large square shutter-release button so the crew could use it while wearing their cumbersome spacesuits.

“The other major modification, was the removal of the viewing screen – because it’s extra glass,” Levasseur says, The astronauts, “had to learn how to take pictures without being able to see anything”, she says. “Without a viewfinder, you can’t see what you’re taking.”

Nasa

NasaTaking photos, says Levasseur, was planned meticulously and written into the mission plan. “They had known previous launches wouldn’t give them whole Earth, but on this one the whole Earth would be entirely illuminated by the light of the Sun.”

It was around five hours and 20 minutes into the flight that the crew got their first glimpse of the entire planet. The crew were starting to get ready for bed, zipping into their sleeping bags. It was their first moment of downtime since the launch.

“I suppose we’re seeing as 100% full Earth as we’ll ever see,” said Cernan. “Bob, it’s these kind of views that stick with you forever… There’s no strings holding it up either. It’s out there all by itself.”

The Blue Marble image was captured at around 29,000km (18,000 miles) from Earth, as the Sun lit up the globe from behind the Apollo 17.

Almost six hours into the flight, Schmitt laughed. “The problem with looking at the Earth, particularly Antarctica, is it’s too bright,” he said, “And so I’m using my sunglasses through the monocular”.

Back home, it was nearing 05:00 at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, and ground control was quiet. “I’m not keeping you awake, am I, Bob?” asked Schmitt. “Just keep talking. We’re listening,” came the voice from the capsule communicator. And so the conversation continued long into the flight, the crew describing the clouds drifting over the ocean and the continents of home.

Nasa

Nasa“If you can’t see something, it’s hard to visualise that it exists,” says Nick Pepin, a climate scientist at the University of Portsmouth in the UK. “I think all of us who have been brought up with that [image] from a young age probably find it difficult to imagine a time when we didn’t know what the Earth looked like. This was the first time that we could actually look back from space and see our home – and people suddenly realised it was an amazing thing, but also a fixed system that we live on.”

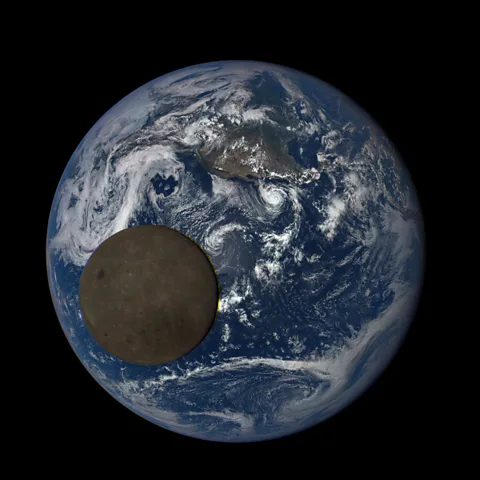

The image offers a view of the Earth from the Mediterranean Sea area to the Antarctica South polar ice cap. Heavy cloud hangs over the Southern Hemisphere, and almost the entire coastline of Africa can be seen.

Nasa

NasaAt 07.39 GMT on 7 December 2022 – 50 years later to the minute since the original was taken – a new “Blue Marble” was captured by a satellite orbiting a million miles away. This time, a set of 12 images taken 15 minutes apart, reveal noticeable changes to our planet’s surface, the result of 50 years of global warming.

In the 50 years that separates these two snapshots in time, one of the most striking differences is the visible reduction in the size of the Antarctic ice sheet. “You can see the shrinking cryosphere – the shrinking ice sheet and the loss of the snow,” says Pepin says. This, he says, is a major indicator of climate change.

Nasa Epic

Nasa Epic“With respect to the Blue Marble, on the 50th anniversary, we decided to take the same images at 15 minute intervals. So, in 15 minutes [the Earth] rotates around maybe 100km (62 miles),” says Marshak. And, thanks to advances in technology, he adds, “we can see the same images, but with much better quality”, even from a million miles away.

Nasa Epic

Nasa EpicThe Dscovr programme hasn’t been running long enough to draw any definitive conclusions, says Marshak, but they are starting to gather data that will provide new insights into how the world is changing – such as changes in cloud cover and height, reflectivity, and vegetation cover.

Among the other changes that have occurred since that first image of the entire Earth 50 years ago is the amount of human development and activity on our planet’s surface. Although not visible in these images of the daylight side of the Earth, other satellites monitor for lights visible on the dark side of our planet. These show dramatic expansions in the urban sprawl across the continents alongside the activity of shipping on the Earth’s oceans. Wildfires also glow across large swathes of the land at night, doubling in frequency in just the past 20 years.

Back in 1972, the Blue Marble prompted a mass-reconsideration of our place in the Universe. Astronauts viewing Earth from space have reported a profound feeling of awe, a sense of interconnectedness and environmental awareness, and of self-transcendence. This is called the “overview effect“.

In the utter vastness of space, the beauty of Earth can be overwhelming. This feeling of intense awe has been found to elicit a fundamental change in thinking, a kind of cognitive realignment also called the “need for accommodation”, as the person attempts to this process new perceptual information.

“Gobsmackingly – just – wow” is how Helen Sharman, the UK’s first astronaut, described her first view of the Earth from space. It was 1991 and the 27-year-old chemist had just launched from Kazakhstan, to begin her journey to the Soviet Mir space station.

Helen Sharman

Helen Sharman“We had two windows on the Soyuz spacecraft,” she says. “The commander, who sits in the middle, doesn’t get a window. But the research cosmonaut, which was my job, and the flight engineer – we both had one. I had the right seat and flight engineer had the left seat. As we were launching, the spacecraft tipped my side very slightly towards the Earth. Immediately, the light streamed through that window.”

Sharman describes her view of the curvature of the Earth, the “gorgeous blue seas”, white clouds, and black space above. The Earth, she says, appeared as if it had its own glow. “The Sun was at quite a low angle, so it would reflect off the sea, and then back up to the clouds – and off the clouds underneath to the Earth. Then [the light] came up so it felt as though the Earth had its own light source.”

She compares the colour to the “ultramarine of renaissance paintings”. “It’s quite unlike the rest of nature. It’s that brightness against the blackness of space, you just see the Earth as this great big gorgeous blue dot.”

Then, as her eyes began to adjust to the darkness of space, the stars appeared in their billions. “We know there are probably billions of stars just in one small section of the Milky Way, maybe even trillions. And we think maybe there could be up to a couple of trillion galaxies in the Universe. That [makes you] realise the insignificance of Earth.”

Sharman experienced these conflicting thoughts all at once. “Our atmosphere is so thin. How easily that whole top layer, where most of life is, could just be wiped away.” But, conversely, she adds, “Earth is not the focal point of the Universe.”

To this day Sharman dreams of “floating along inside one of the modules and stopping by a window, looking out with the other crew”. The experience of viewing the Earth from space, she says, “definitely changed my life’s priorities”. “The most important thing is the people. And of course, the environment and ecology that’s required to keep this Earth going.”

Nasa Epic

Nasa EpicThe Blue Marble was used to illustrate the Gaia hypothesis, developed in the 1960s and ’70s, which proposes that Earth and its biological systems act as a huge single entity, that exists in a delicate state of balance. And, although controversial among scientists, the theory kickstarted a holistic approach to Earth Science.

The photograph appeared on postage stamps, and in the opening sequence of former US vice president Al Gore’s documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, and inspired research into Earth systems with the establishment of climate research institutions such as the Max-Planck Institut, based in Munich, Germany.

Simon Mtuy

Simon MtuyLooking at the 1972 and 2022 Blue Marble images side-by-side, Pepin describes the Earth’s “restless atmosphere”. Visible in both images, are clouds formed above the green areas of rainforest, demonstrating the inextricable link between the forests and the rain. “If you look at [central] Africa, you can see that most of the cloud, particularly on the earlier [image] is quite spotty, that indicates thunderstorms. Whereas if you go further north, and look at the Sahara desert, you can see there are no clouds.

“When you look from above you see all the connections, the overall relationships between areas,” says Pepin. “For example, Kilimanjaro rises from grassland, with snow on top. If you lived on the slopes you might not know there was snow on top and the importance of the connection between those areas.”

Looking at the Earth from space like this, he says, “makes you appreciate the interlinkages between different parts of the ecosystems”. “If you can only see your bit, you might think that environmental problems are only happening somewhere else and assume that ‘it’s not my problem’,” says Pepin.

However, the limitation, he says, is scale. “You lose the detail. You need both. You need ground truthing [validating the information in the field] too.”

Nasa

NasaThere is a “huge fundamental difference” between these two images though, says Levasseur. “One is captured by a human – and one is not. It doesn’t have the same impact. And that’s really because of the fact that there’s no person there.”

Levasseur is looking forward to the photographs that will be brought home from the next manned mission to go as far as the Moon: Artemis II, planned for 2026. “There’s not going to be another whole Earth image in the way I think of it until humans go out away from Earth again. I wasn’t alive in 1972. This is going to be a huge moment to know that people are looking at us from that far away.”

“As much as we like to think of satellites as sort of our surrogates,” she says, “I know that there is a person behind that camera, so there is something different about it, and there always will be.”