A window into how visible matter emerges from the “nothing” of vacuum has been opened by physicists at the Brookhaven National Laboratory’s Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) in New York.

The researchers found that particles of matter emerging from high-energy subatomic collisions often retain a key feature—particle spin—of the “virtual particles” that exist only fleetingly in the quantum vacuum.

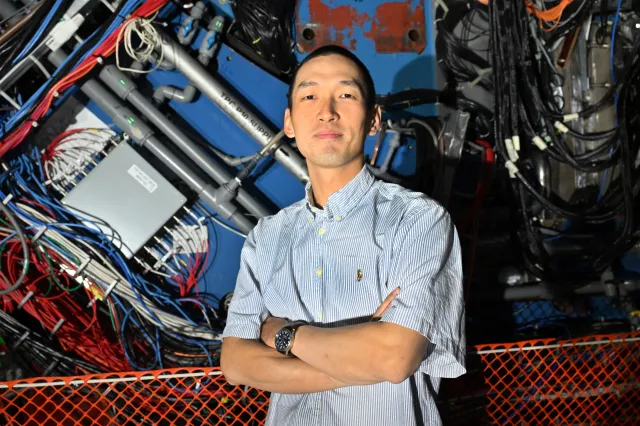

“This work gives us a unique window into the quantum vacuum that may open a new era in our understanding of how visible matter forms and how its fundamental properties emerge,” said paper author and physicist Zhoudunming (Kong) Tu in a statement.

As conceived under classical physics, the vacuum is a completely empty region of space—one devoid of energy, matter and physical fields.

In the last century, however, a new understanding of the vacuum has emerged. Under quantum mechanics, the vacuum is anything but empty.

Instead, vacuum is now believed to be filled up with fluctuating energy fields that can briefly form entangled pairs or particles and their antimatter opposites which, in essence, “borrow” energy from the vacuum.

These pairs are considered to be “virtual”—rather than “real”—in nature and, in most cases, they have but a fleeting existence before they annihilate each other.

In the high-energy proton-proton collisions in the RHIC, however, some of these virtual particle pairs gain enough energy to become real components of detectable particles.

In the new study, the researchers sought out a particular product of proton-proton collisions—so-called “lambda hyperons” and their antimatter counterparts, “antilambdas.”

The team wants to determine if—and to what extent—the spins of these particles are aligned in the wake of the collisions in the RHIC.

Spin as a property is something of a misnomer; while it might sound like particles whizz around like tops, in reality, spin is an intrinsic quantum property that acts more a marker, causing the particles to behave as if they were spinning in terms of both angular momentum and magnetism.

Lambda particles are a great choice for studying spin, because the direction of their spins can be calculated from the direction of the protons or antiprotons that they produce when they decay.

On top of this, lambda are each also made up with either a strange quark or a strange antiquark, allowing physicists to trace back the particle’s origins.

When strange quark-antiquark pairs are generated from the vacuum as virtual particles, their spins are always aligned—unlike the majority of particles generated in proton-proton collisions, which end up with no set spin direction.

Accordingly, if lambda and antilambda particles emitted together in the wake of a particle collision have aligned spins, it would provide strong evidence of a connection to spin-aligned virtual strange quark pairs emerging from the vacuum.

“We are looking for a very tiny difference from all those other particles to find lambda/antilambdas where their spins are correlated,” said paper author and physicist Jan Vanek of the University of New Hampshire in a statement.

After wading through data on millions of proton-proton collision events, the physicists determined that, when lambda and antilambda particles emerge close together in the wake of a collision, they do so completely spin-aligned, just like virtual strange quark/antiquark pairs in the vacuum.

This suggested that the strange quark/antiquark particles in the lambda/antilambda particles emerged as an entangled pair—retaining a spin linkage that was established in the vacuum.

According to the researchers, the energy of the particle collisions in the RHIC gives the “virtual” particles the energy boost they need to transform into “real” particles.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to see directly that the quarks that make up these particles are coming from the vacuum—it’s a direct window into the quantum vacuum fluctuations,” said Tu.

“It’s amazing to see that the spin alignment of the entangled virtual quarks survives the process of transformation into real matter.”

“It’s as if these particle pairs start out as quantum twins,” Vanek added. “When they’re generated close together, the lambdas retain the spin alignment of the virtual strange quarks from which they were born.”

It is possible that this spin linkage reflects a deeper entanglement between the lambda-antilambda pairs, a connection that could endure even when the particles are separated.

That said, the team also notes that the spin correlation disappears when lambda/antilambda pairs are found farther apart after proton-proton collisions.

“It could be that these twins sent farther away from each other are more affected by other things in their environment—interactions with other quarks, for example—that cause them to behave differently and lose their connection,” said Vanek.

“We need further measurements to see if this is a mix of entangled states or a more classically correlated system.”

Regardless of the answer to this question, the connection between entangled quarks in the quantum vacuum and ordinary particles detected in the wake of particle collisions could offer a window through which to observe the transition from quantum to classical states of matter.

Insights here, the team says, would be important for quantum information science and the development of future quantum-powered technologies.

Furthermore, learning how quarks transform from free-moving entities into the building blocks of subatomic particles like protons, neutrons and hyperons provides a new path to explore fundamental questions about how mass and structure emerge in the universe.

“In our experiment, the energy needed to transform virtual particles from the vacuum into real matter comes from the RHIC collisions,” said Tu. “Now, we can reverse engineer it to explore this complicated process.”

This is one of the biggest mysteries faced by humankind, Tu said, that of “how something—the visible matter of our universe—connects to the ‘nothingness’ of the vacuum.”

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about particle physics? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Reference

STAR Collaboration. (2026). Measuring spin correlation between quarks during QCD confinement. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09920-0