Hannah Roller

The best teacher I have ever had is my mother’s father. Bill Fields, my grandfather, has dedicated the entirety of his professional life to education. He spent 42 years teaching social studies at Monument Mountain, a small public high school in rural Massachusetts. When he retired in 2006, he worked for three more years as a substitute teacher there. In 2014, he was elected to the school committee, campaigning on a platform that advocated against standardized testing. During that term, he was the only retired teacher representing the school. He ran again in 2018 and was written in — despite attempting to retire, this time for real — in 2022. He serves on the school committee to this day. Education, to him, is not simply a career or a way to make ends meet, but a distinct, powerful and lifelong vocation.

As I began college I often found myself considering the value of higher education. In today’s world, a degree does not guarantee a secure job and future. Trade school could offer a faster path to a paycheck, less debt and immediate employment. Higher education has faced increasing critiques, from society and the federal government, as some argue that it yields high student loans and not much else. So, what is the point? To answer this question, I found myself turning to my grandfather, a person entirely convinced of the value of education.

Bill graduated Springfield College in 1969 after majoring in education with a concentration in history. He attended graduate school at the University of Massachusetts and received his masters in 20th century history in 1972. While he worked towards his master’s, he began working at Monument, where he taught social studies to grades nine through 12. Every social studies teacher he worked with had a history degree, which meant the department had a unique passion. It was a space of debate and critical inspection of the surrounding world. The teachers engaged with the students in a way that forced them to form opinions and stake a claim. He taught classes on historical classics, the American Revolution and the Holocaust — one of the first such classes in the nation.

A few weeks ago, while FaceTiming him as I folded my laundry, I asked him what led him to the classroom. He reflected on the role of education in his own life.

My grandfather attended public school from kindergarten to eighth grade before switching to the rigid and traditional world of an all-boys private school for high school. This exposure to different schooling atmospheres allowed him to learn alongside classmates of varying levels of privilege and academic focus, forcing him to consider different perspectives on the world.

The transformative nature of education steered him to teaching. “I wanted to kind of better the community and help these kids find themselves as they grew older,” he told me, to “give them some background, and knowledge and context.” He found great meaning and satisfaction in helping a kid grow — he would intentionally challenge them, forcing them to articulate their thoughts through writing and debate. He taught in a way that gave even his most reluctant students no choice but to interact with history, humanizing a subject that is often thought of as dry facts, old historical figures and memorized dates. To him, history is essential in interpreting the world, and learning it provides a critical context essential for life regardless of one’s ultimate career.

This deeper, philosophical approach to teaching was incredibly fulfilling for Bill. Instead of a system of information in and information out, he directly interacted with his students, helping them realize the pertinence of their education to their own lives.

In the mid ’70s, a Monument freshman was killed in a drunk driving accident on the weekend of graduation. The community was reeling, but many teachers, unsure of how to navigate the tragedy, kept teaching, business as usual. My grandfather didn’t teach that day. Instead, he sat with his students while having candid conversations about grief and morality. He went home that day taken aback by how little opportunity students of that age have to consider morality. After discussing it with his wife, he decided it should be worked into a course.

“Life and Death,” initially named “Death: Your Only Sure Future,” became my grandfather’s trademark class. It is the one that alumni always mention to me when they find out that I’m related to Mr. Fields. In the class, students read “A Man’s Search for Meaning” by Victor Frankl, wrote obituaries and visited the local funeral home.

“Many students have told me they really enjoyed this course because it made them think about their life and they were respected for their thoughts,” he said, which was refreshing since “most people didn’t think it was important for them at their age to be thinking about death and their life.”

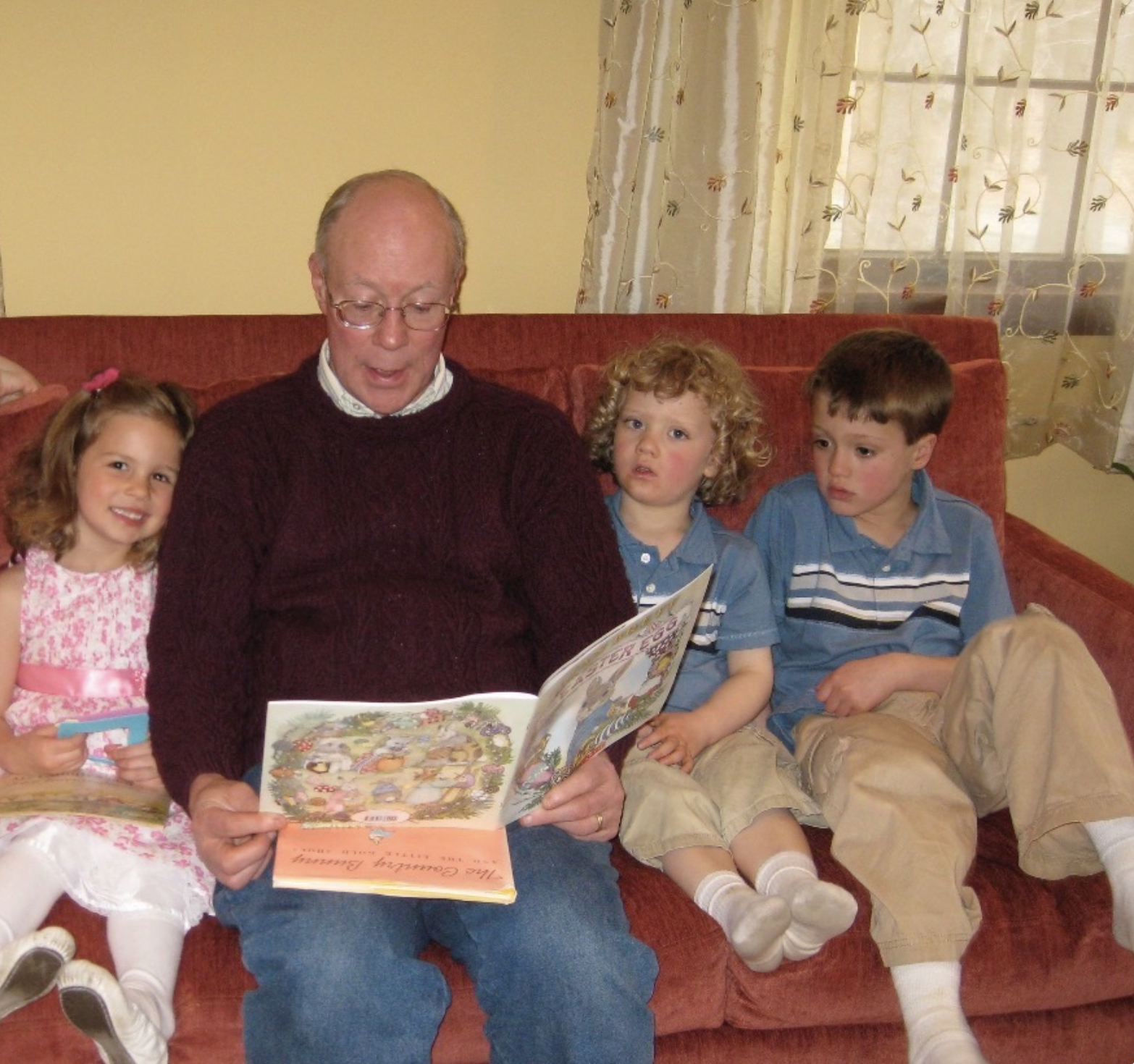

My grandfather taught me social studies over Zoom in eighth grade. Throughout my own four years at Monument, I would often run into him in the halls. He was always visiting the principal, or a teacher, or dropping off a book. It is impossible for him to go to the supermarket without running into an old student or colleague (and therefore entering into a long discussion). His walls are lined with history books. He can flawlessly describe complex historical nuance, immediately remember the date of a war or treaty and tell you exactly where a student sat in his classroom. Teaching has permeated his life; it is inextricable with his being.

I asked him if education is essential to a meaningful life. He responded yes, but that the key is to remember that education is broad. To him, education allows for deep and specialized knowledge of a facet of the world. Learning to read, for example, is essential to becoming a well-equipped and critical citizen. He emphasized that technical education, such as the training an electrician or auto mechanic would receive, is just as valuable to a meaningful career and life as medical school is to a doctor. Regardless of its form, education is a necessity.

“The idea of being educated has made me more in touch with being human,” he tells me when I ask him how working in education has shaped him. He deeply believes, and has personally witnessed, that pursuing learning and knowledge is needed for the formation of a human. Continuing one’s education, he reminds me, allows us the opportunity to dig deeper, more critically and more purposefully into our interests and quandaries. Perhaps this is the true purpose of higher education: to allow one a deep encounter with the world.